Software tools for Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Lesson 4 - Basic random effects in RTMB

11 December 2023

Outline:

- Overview of purpose of lesson

- What is a random effect

- MLE random effect theory

- The Laplace approximation

- A brief mention, SE in RE models

- Basics of R code to implement random effects

- A first random effects application

Overview/purpose

- learn some basic RE concepts

- learn how to implement a RE model in RTMB

In large purpose we avoid the technical details underlying how TMB addresses technical challenges of AD combined with the Laplace transformation. I refer you to Kristensen et al. (2016) an open source pub for more technical material: https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v070i05

What is a random effect

- Random effects seem something like parameters

- But for maximum likelihood estimation parameters cannot be random

- Hence we distinguish (fixed) parameters from random effects

- ultimately (fixed) parameters determine the distributions for REs

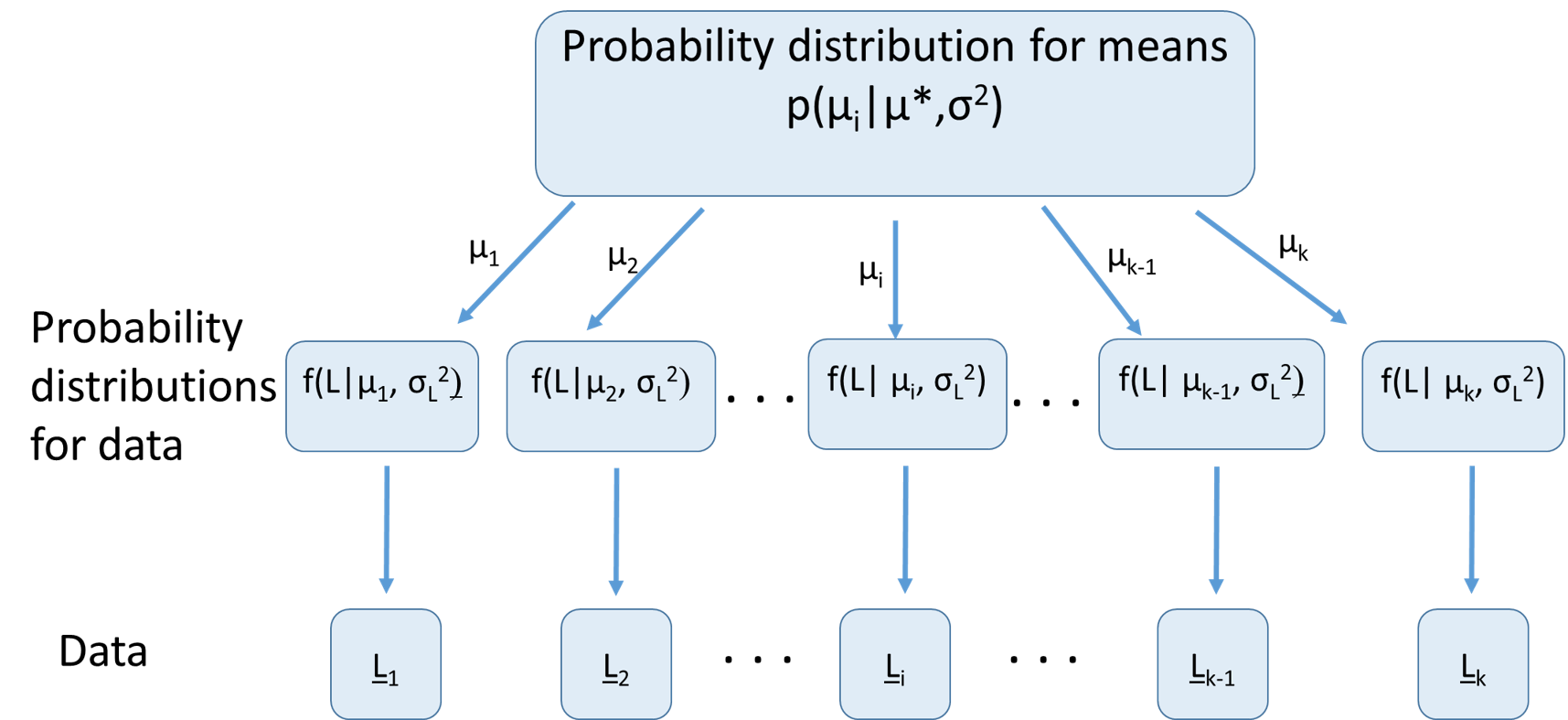

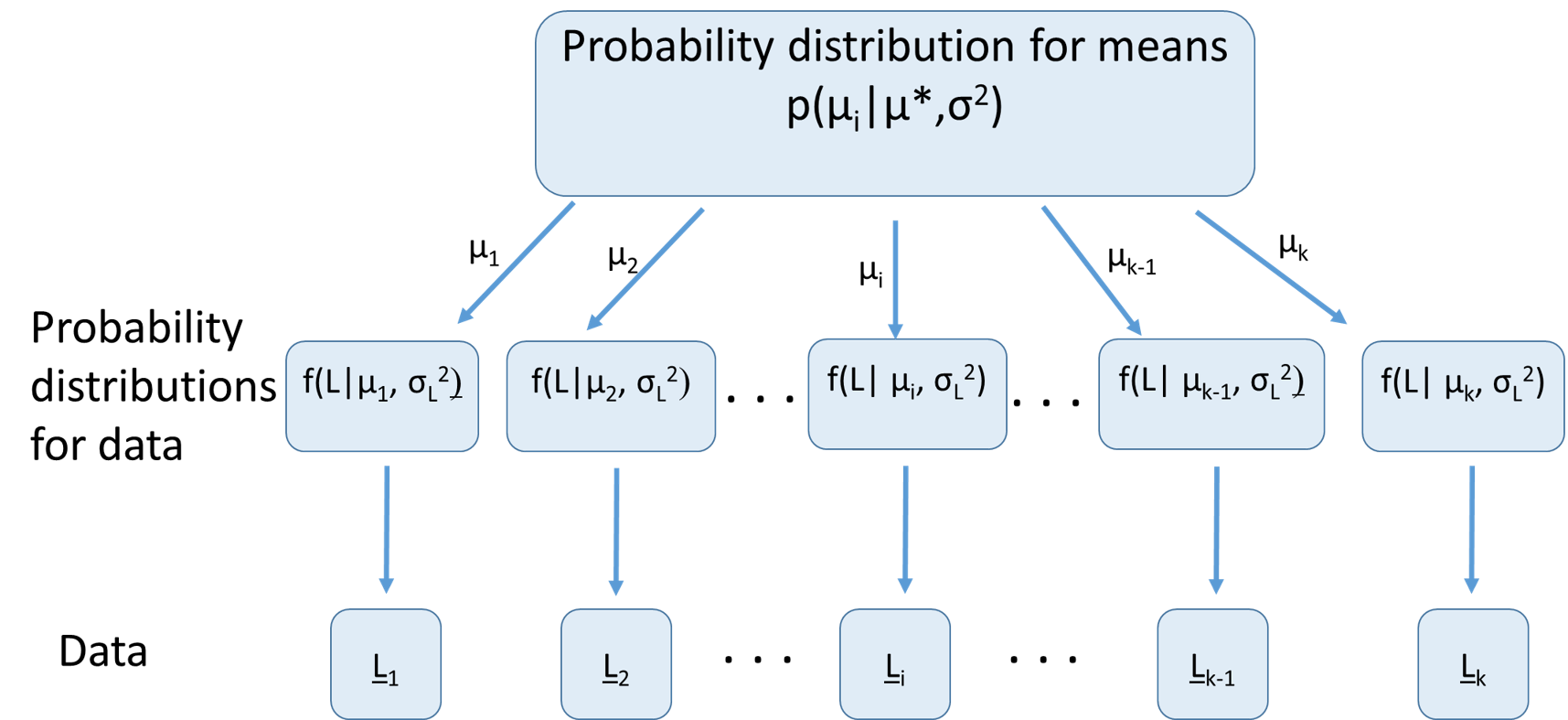

Graphical example of RE model

Advantages of models with REs

Assuming REs come from a common distribution shares information is shared. E.g., if we know mean length across a number of ponds, we have information about likely mean length in a poorly sampled pond

Sometimes we can analyze data that could not be analyzed with a fixed effect model

- E.g., if an interaction term is viewed as fixed then it requires data for every combination of factors

Inferences can be more general (about the distribution from which the random effects arose)

The strength could become a liability

If dissimilar things are combined.

- You can only share information if there is information to share. E.g., combining 9 bluegill populations and 1 shark population. Does mean length of bluegills tell us much about shark length… Duh!

Too few instances of the random effects to estimate their distributional parameters

MLE Random Effects Theory

The joint likelihood (sometimes aka penalized likelihood)

The marginal (true) likelihood

Why we want to maximize marginal likelihood

The joint likelihood

\[ L(\underline{\theta}, \underline{\gamma} \mid \underline{X})=L\left(\underline{\theta} \mid \underline{\gamma}, \underline{X}\right) p\left(\underline{\gamma} \mid \underline{\theta}\right) \]

Joint likelihood found by taking product of the likelihood conditioned on both RE (\(\underline{\gamma}\)) and data (\(\underline{X}\)) and pdf for random effect conditioned on parameters

Maximizing the joint likelihood is sometimes called penalized likelihood. Basically treats random effects like parameters.

- Substantial limitations and drawbacks to doing this

Marginal likelihood

\[ L(\underline{\theta} \mid \underline{X})=\int_{\underline{\gamma}} L(\underline{\theta}, \underline{\gamma} \mid \underline{X}) d \underline{\gamma}=\int_{\underline{\gamma}} L\left(\underline{\theta} \mid \gamma, \underline{X}\right) p\left(\underline{\gamma} \mid \underline{\theta}\right) d \underline{\gamma} \]

Computationally intensive (integrate over all possible values for the random effects)

Only feasible for complex models in last ~15 years due to software advances

- “smart” AD, implementation of Laplace approximation

Fortunately in RTMB we only have to specify the log of the joint likelihood

Collect together the pieces of log joint likelihood and add them up!

The Laplace approximation

\[ L^{*}(\underline{\theta})=\sqrt{2 \pi^{n}} \operatorname{det}(H(\underline{\theta}))^{-\frac{1}{2}} \exp (-g(\underline{\theta}, \underline{\widehat{\gamma}})) \]

- With \(\underline{\theta}\) fixed at current values, adjust \(\gamma\) to find \(\underline{\widehat{\gamma}}\) that minimizes the neg log joint likelihood \(g(\underline{\theta},\underline{\gamma})\).

- \(H(\underline{\theta})\) is the matrix of second/cross derivatives calculated for the combined vector {\(\underline{\theta},\widehat{\underline{\gamma}}\)}. Written this way to emphasize its function of current value of params

- In the background, during minimization, at each step TMB does an inner minimization to find \(\widehat{\underline{\gamma}}\) so it can apply the Laplace approximation.

Asymptotic standard errors

- Previously we have discussed the delta method used to get asymptotic SEs to for derived quantities in fixed effect models. TMB has implemented an adaptation of those methods for estimating SEs for random effects and quantities that involve them, that accounts for uncertainty in the fixed effects (see Skaug and Fournier, 2006: Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 56, 699–709. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2006.03.005)

What you need to do in R code

Create a character vector, with the values equaling names of “parameters” you want to be treated as random

These must match exactly names you used for parameters in our parameter list.

Technically what declaring a parameter as random does is ask TMB to integrate it out of the likelihood. The distribution is specified in the function you minimize

Modify your “NLL function” so it returns the negative joint likelihood. This involves subtracting terms equal to log of density for the random effects. This sounds more complicated than it is.

Simple random effects example

Unrealistic example to keep data management dead simple. One observation of length at each age (2-12) for each pond (arranged in a matrix).

fit vonB model for length at age, but now assume asymptotic length (Linf), rather than being a single number, varies among ponds, with the log of Linf for each pond coming from a common normal distribution.

Assume observed length at age normally distributed, with mean generated from the vonB function for that pond (and age), and a common SD shared over ages and ponds.

Before we proceed, what are the parameters (excluding the pond specific Linfs that are now random effects)?

Some exercises

Make log_vonbk rather than log_linf a random effect (so now just one log_linf not random)

Estimate Linf for each pond as a fixed effect rather than a random effect

AIC is calculated as 2k-2*NLL, where k is the number of estimated parameters and NLL is the true (marginal) likelihood. See if you can figure out how to calculate this.