library(tidyverse)

library(ggqfc)

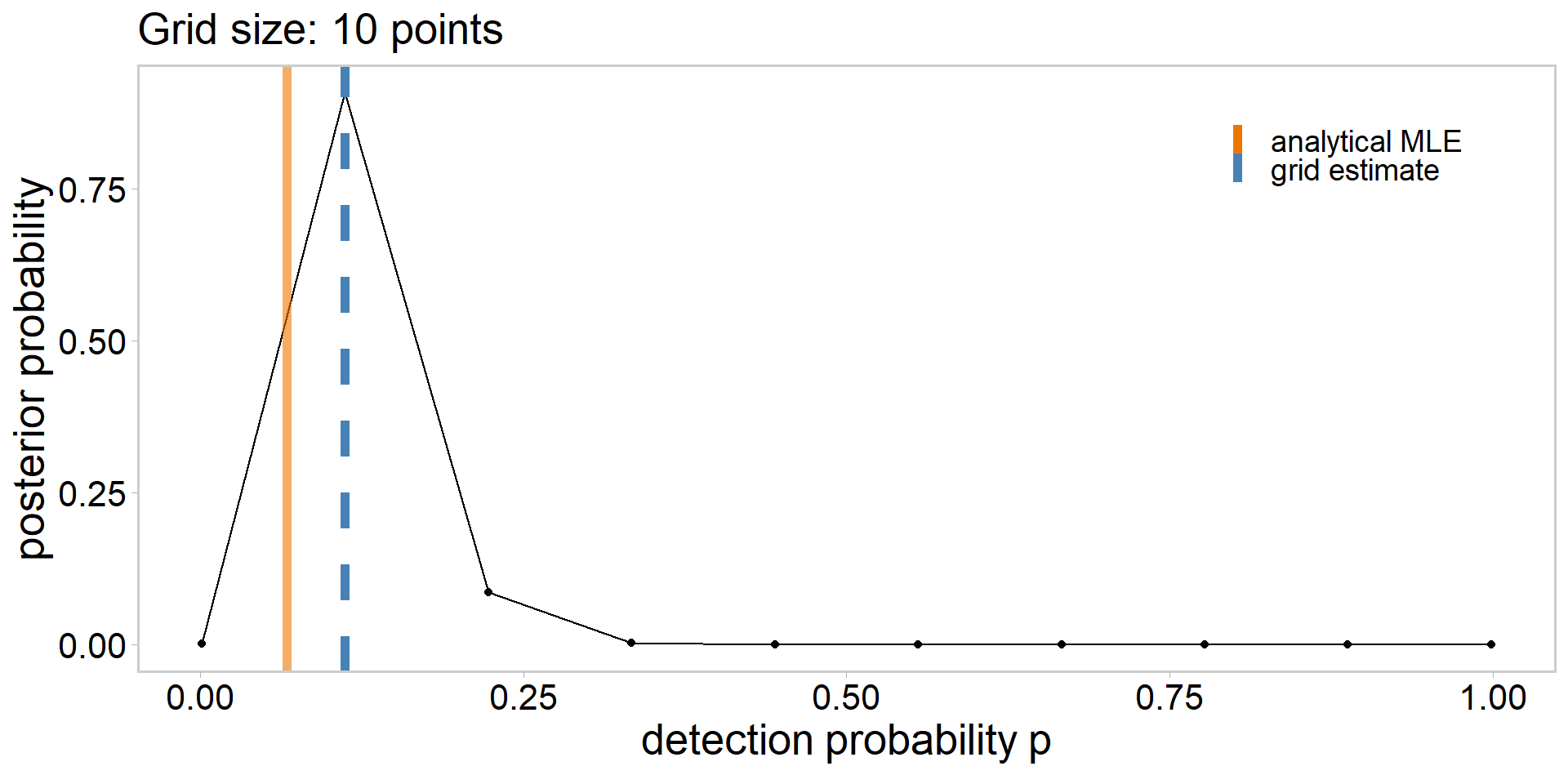

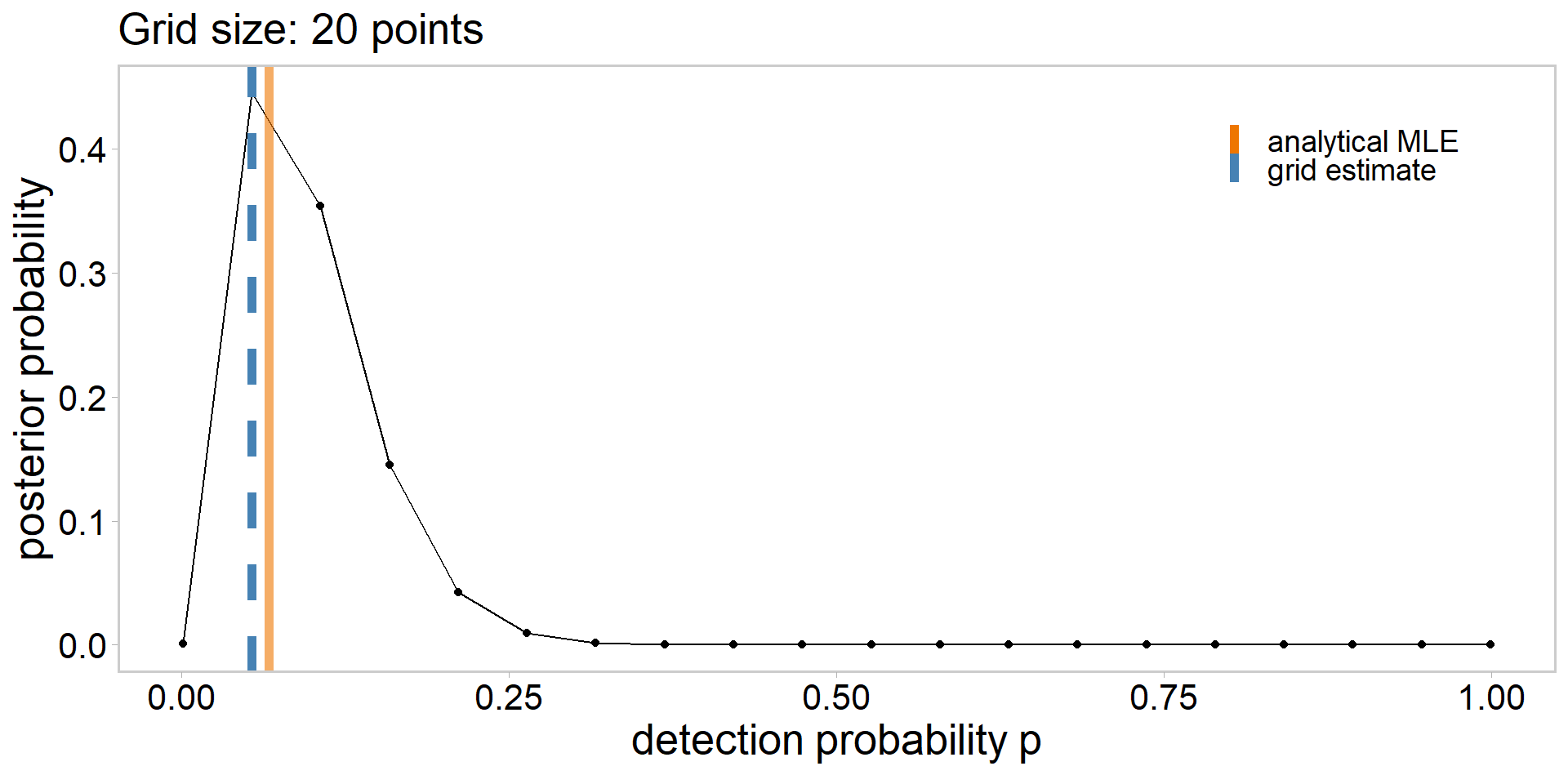

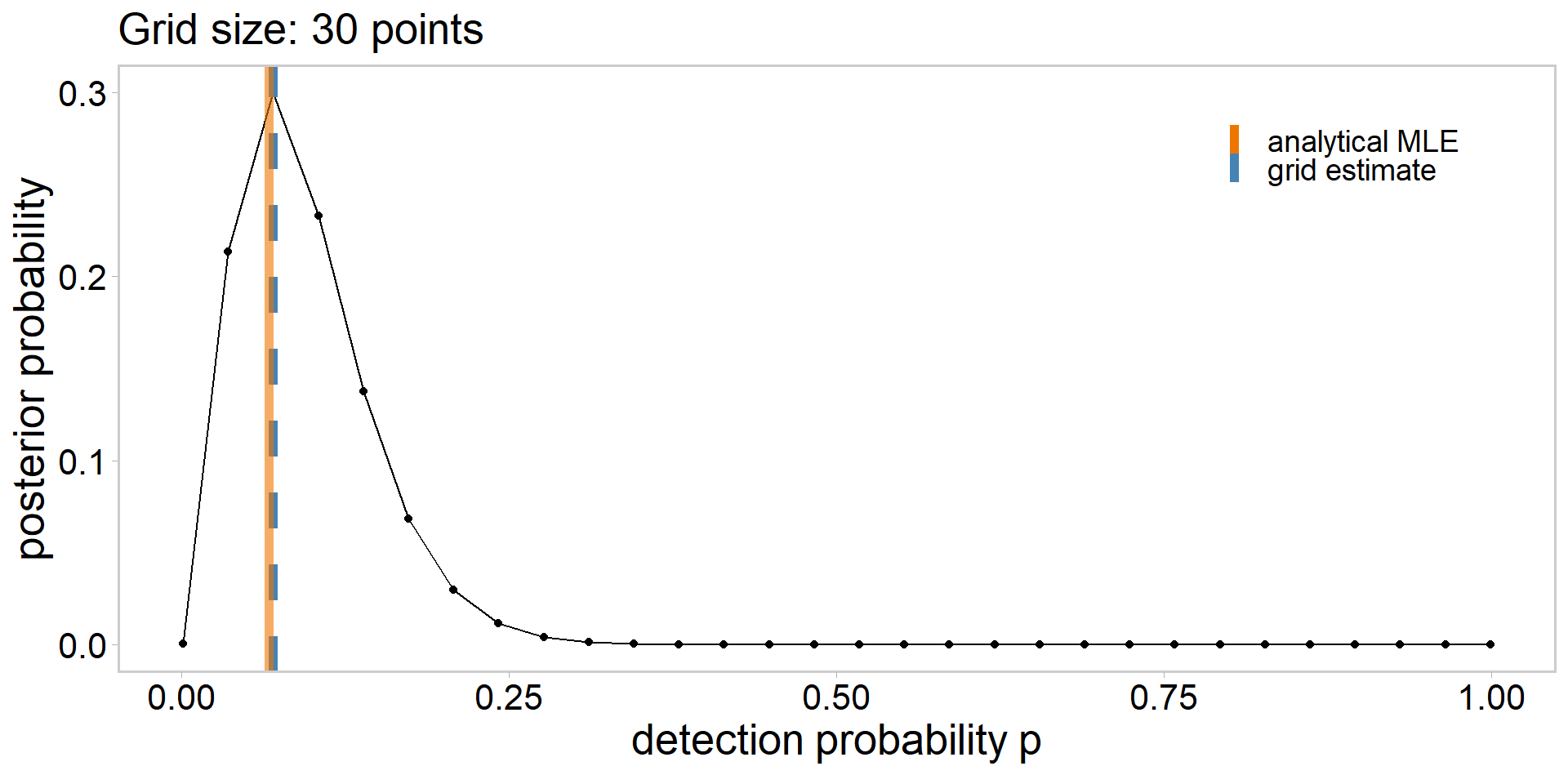

y <- c(

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

) # sucesses (turtle detections)

n <- length(y) # trials

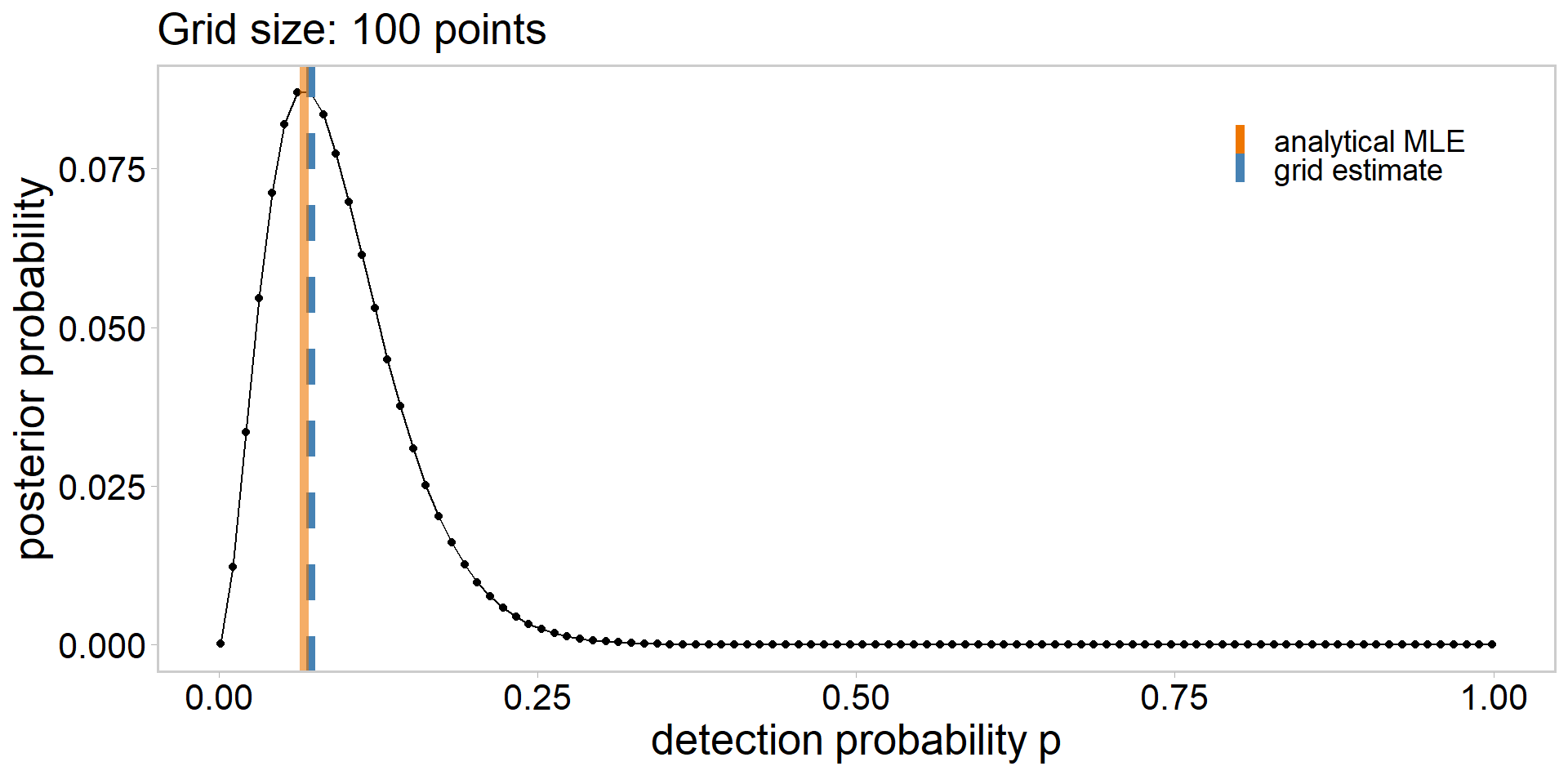

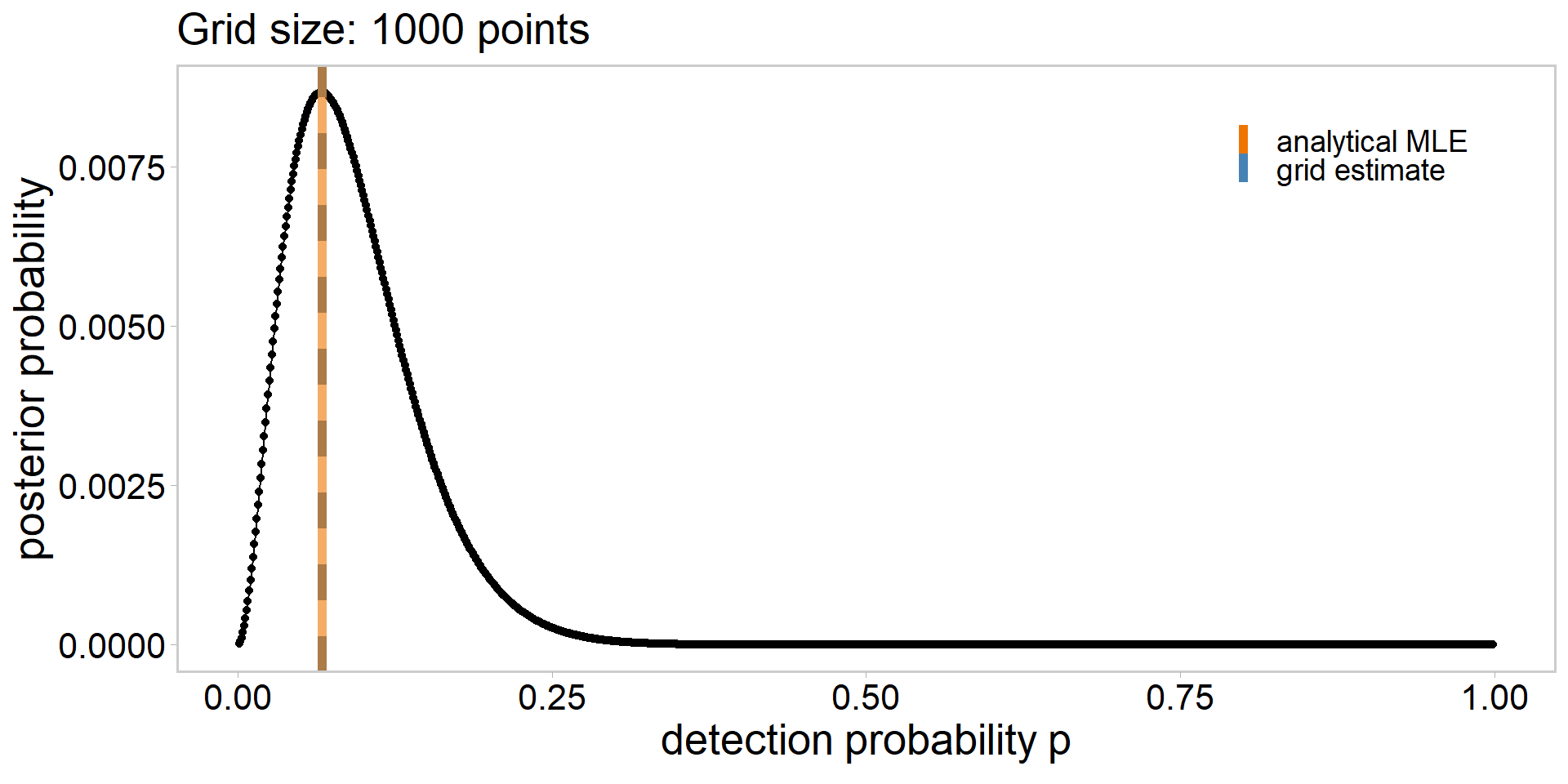

# define a grid

grid_size <- 10

p_grid <- seq(from = 1e-3, to = 0.999, length.out = grid_size)

# calculate likelihood

lik <- dbinom(sum(y), n, p_grid)

lik # likelihood of having observed the data | each p_grid value [1] 4.229830e-04 1.964028e-01 1.859940e-02 5.603740e-04 6.085257e-06

[6] 1.860800e-08 8.682232e-12 1.445413e-16 7.970008e-25 4.341304e-82