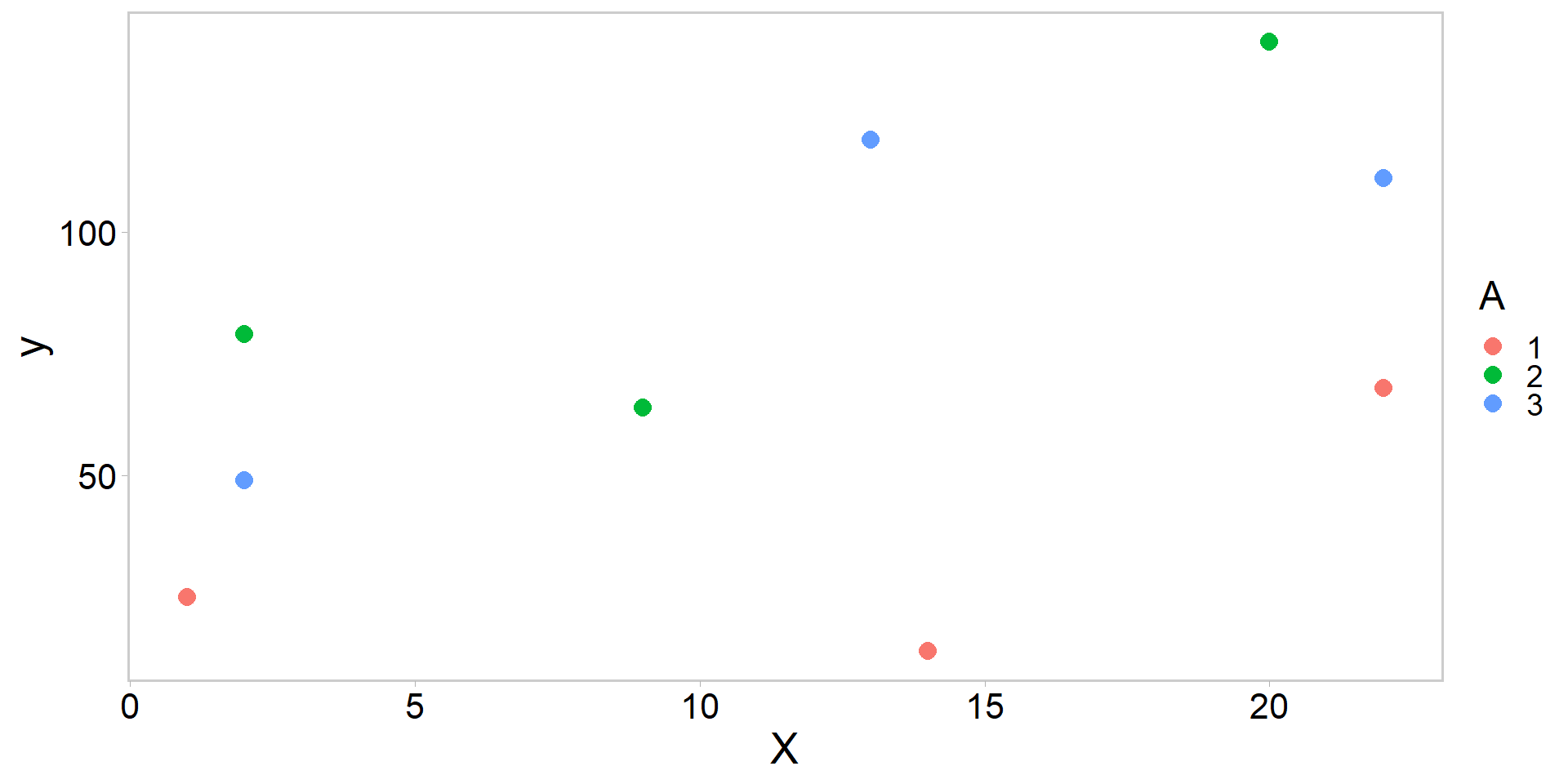

library(tidyverse)

library(ggqfc)

y <- c(25, 14, 68, 79, 64, 139, 49, 119, 111) # obs

A <- factor(c(1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3)) # group

X <- c(1, 14, 22, 2, 9, 20, 2, 13, 22) # covariate

my_df <- data.frame(y, A, X)

my_df %>%

ggplot(aes(X, y, color = A)) +

geom_point(pch = 16, size = 3.5) + theme_qfc()An introduction to Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

FW 891

Click here to view presentation online

11 September 2023

Purpose

- Introduce design matrices for linear models

- Introduce Generalized Linear Models

- In particular, the Poisson and binomial GLMs

- Simulate fake data from these models

- Write Stan code to estimate the parameters of these models

- A fun question

Breaking statistical models down

response = deterministic component + random component

- This section / lecture is based heavily on Kery and Schaub 2012; Kery and Royle 2016

The random (noise) component

- Hallmark of statistical models: they must account for randomness

- Check out ?ddist in R, and replace dist by any of the following: pois, binom, norm, multinom, exp, and unif

- Changing first letter d to p, q, or r allows one to get the density, the distribution function, the percentiles, and random numbers from these distributions, respectively.

- Note R calls mass functions density functions (e.g.,

dbinom())

- Note R calls mass functions density functions (e.g.,

Kery and Schaub 2012; Kery and Royle 2016

The deterministic (signal) component

- The signal component of the model contains the predictable parts of a response or the mean structure of a model

- Often the mean structure is described by a linear model, although nonlinear models can also be used (Seber and Wild 2003)

- Linear model is just one specific way to describe how we imagine our explantory variables influencing our repsonse

- This model is linear in the parameters and does not need to represent a straight line when plotted

- t-test, simple and multiple linear regressions, ANOVA, ANCOVA, and many mixed models are all linear models

Kery and Schaub 2012; Kery and Royle 2016

A brief illustration of an analysis of covariance ANCOVA

A brief illustration of an analysis of covariance ANCOVA

Running the (Frequentist) ANCOVA in R

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ A - 1 + X)

Coefficients:

A1 A2 A3 X

1.315 65.218 58.648 2.785 - This so-called “formula language” is clever because it is quick and error-free if you know how to specify your model

- What does y ~ A−1 + X actually mean?

Kery and Schaub 2012; Kery and Royle 2016

ANCOVA maths

- When we fitted that model, we were doing the following:

\[ y_{i}=\beta_{g(i)}+\beta_{1} \cdot X_{i}+\varepsilon_{i} \quad \text {where} \quad \varepsilon_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right) \]

- \(y_{i}\) is a response of unit (data point, individual, row) \(i\), \(X_{i}\) is the value of the continuous explanatory variable \(x\) for unit \(i\)

- Factor \(A\) codes for the group membership of each unit with indeces \(g\) for groups 1,2, or 3

- Two parameters in the mean relationship, \(\beta_{g(i)}\) and \(\beta_{1}\)

- First of these is a vector, second a scalar

- Index \(g\) indicates group 1, 2, or 3

ANCOVA maths: one way

\[ y_{i}=\beta_{g(i)}+\beta_{1} \cdot X_{i}+\varepsilon_{i} \quad \text {where} \quad \varepsilon_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right) \]

- The random (noise) part of the model consists of the part of the response which we cannot explain using our linear combination of explanatory variables

- Represented by residuals \(\varepsilon_{i}\)

- Assume they come from a normal distribution with common variance \(\sigma^{2}\)

- How many parameters in total does this model have?

ANCOVA maths another way

Old way:

\[ y_{i}=\beta_{g(i)}+\beta_{1} \cdot X_{i}+\varepsilon_{i} \quad \text {where} \quad \varepsilon_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right) \]

Shifting the structure of the model via algebra:

\[ y_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(\beta_{g(i)}+\beta_{1} \cdot X_{i}, \sigma^{2}\right). \]

ANCOVA maths even more ways

A further possibility:

\[ y_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(\mu_{i}, \sigma^{2}\right), \quad where \quad \mu_{i} = \beta_{g(i)}+\beta_{1} \cdot X_{i} \]

- Being able to write a linear model in algebra helps code the model in Stan (or any other modeling platform)

- Also helps you understand commonalities between many common statistical tests and what

lm()in R is doing

ANCOVA: but wait, there’s more 🥴🤔

The same model via matrix and vector notation:

\[ \left(\begin{array}{l} 25 \\ 14 \\ 68 \\ 79 \\ 64 \\ 139 \\ 49 \\ 119 \\ 111 \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll} 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 14 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 22 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 9 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 20 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 13 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 22 \end{array}\right) \times\left(\begin{array}{l} \beta_{g = 1} \\ \beta_{g = 2} \\ \beta_{g = 3} \\ \beta_{1} \end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l} \varepsilon_{1} \\ \varepsilon_{2} \\ \varepsilon_{3} \\ \varepsilon_{4} \\ \varepsilon_{5} \\ \varepsilon_{6} \\ \varepsilon_{7} \\ \varepsilon_{8} \\ \varepsilon_{9} \end{array}\right) \text {, with } \varepsilon_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right) \] - Left to right: response vector, design matrix, parameter vector, residual vector

ANCOVA: but wait, there’s more 🥴🤔

The same model via matrix and vector notation:

\[ \left(\begin{array}{l} 25 \\ 14 \\ 68 \\ 79 \\ 64 \\ 139 \\ 49 \\ 119 \\ 111 \end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll} 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 14 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 22 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 9 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 20 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 13 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 22 \end{array}\right) \times\left(\begin{array}{l} \beta_{g = 1} \\ \beta_{g = 2} \\ \beta_{g = 3} \\ \beta_{1} \end{array}\right)+\left(\begin{array}{l} \varepsilon_{1} \\ \varepsilon_{2} \\ \varepsilon_{3} \\ \varepsilon_{4} \\ \varepsilon_{5} \\ \varepsilon_{6} \\ \varepsilon_{7} \\ \varepsilon_{8} \\ \varepsilon_{9} \end{array}\right) \text {, with } \varepsilon_{i} \sim \operatorname{N}\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right) \]

- The value of the linear predictor for the first data point is given by \(1 \cdot \beta_{g = 1}+0 \cdot beta_{g = 2} +0 \cdot beta_{g = 3} +1 \cdot \beta_{1}\)

A trick for learning about the design matrix in R: model.matrix()

A1 A2 A3 X

1 1 0 0 1

2 1 0 0 14

3 1 0 0 22

4 0 1 0 2

5 0 1 0 9

6 0 1 0 20

7 0 0 1 2

8 0 0 1 13

9 0 0 1 22

attr(,"assign")

[1] 1 1 1 2

attr(,"contrasts")

attr(,"contrasts")$A

[1] "contr.treatment"- see also effects or treatment contrast parameterization

model.matrix(~ A + X)

for more information on linear model see: Kery 2010

The ANCOVA in Stan

- The code looks very similar to the algebraic specification of this linear model

- Note I am picking vague-ish priors but the specific priors aren’t the point of this lesson

The ANCOVA.stan file

data {

int<lower=0> n_obs; // number of observations = i

int<lower=0> n_col; // columns of design matrix = j

vector[n_obs] y_obs; // observed data

matrix[n_obs, n_col] X_ij; // design matrix: model.matrix(~A-1+X)

}

parameters {

vector[n_col] b_j; // one parameter for each column of Xij

real<lower=0> sig; // sigma must be postive

}

model {

vector[n_obs] y_pred; // container for mean response

b_j ~ normal(0,100); // priors for b_j

sig ~ normal(0,100); // prior for sig

y_pred = X_ij * b_j; // linear algebra sneakery

y_obs ~ normal(y_pred, sig); // likelihood

}And the corresponding R code:

library(cmdstanr)

mod <- cmdstan_model("week3/soln_files/ANCOVA.stan") # compile

# names in tagged list correspond to the data block in the Stan program

X_ij <- model.matrix(~ A - 1 + X)

stan_data <- list(n_obs = nrow(X_ij), n_col = ncol(X_ij),

y_obs = my_df$y, X_ij = as.matrix(X_ij)

)

# write a function to get starting values

inits <- function() {

list(

b_j = jitter(rep(0, ncol(X_ij)), amount = 0.5),

sig = jitter(10, 1)

)

}

fit <- mod$sample(

data = stan_data,

init = inits,

seed = 1, # ensure simulations are reproducible

chains = 4, # multiple chains

iter_warmup = 1000, # how long to warm up the chains

iter_sampling = 1000, # how many samples after warmp

parallel_chains = 4 # run them in parallel?

)- Note this is all in the solution file for this week

Break

- Now we will move into Generalized Linear Models (GLM), where all of the information we just learned still applies

- Primary difference for GLMs is that they will allow us to model non-normal response variables in a manner similar to what we just did with an ANCOVA

- Do this via a

linkfunction

- Do this via a

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

- The GLM is a flexible generalization of linear regression, developed by Nelder and Wedderburn in 1972 while working together at the Rothamsted Experimental Station in the U.K.

- Extend the concept of linear effect of covariates to response variables for statistical distributions where something other than a normal is assumed

- e.g., Poisson, binomial/Bernoulli, gamma, exponential, etc.

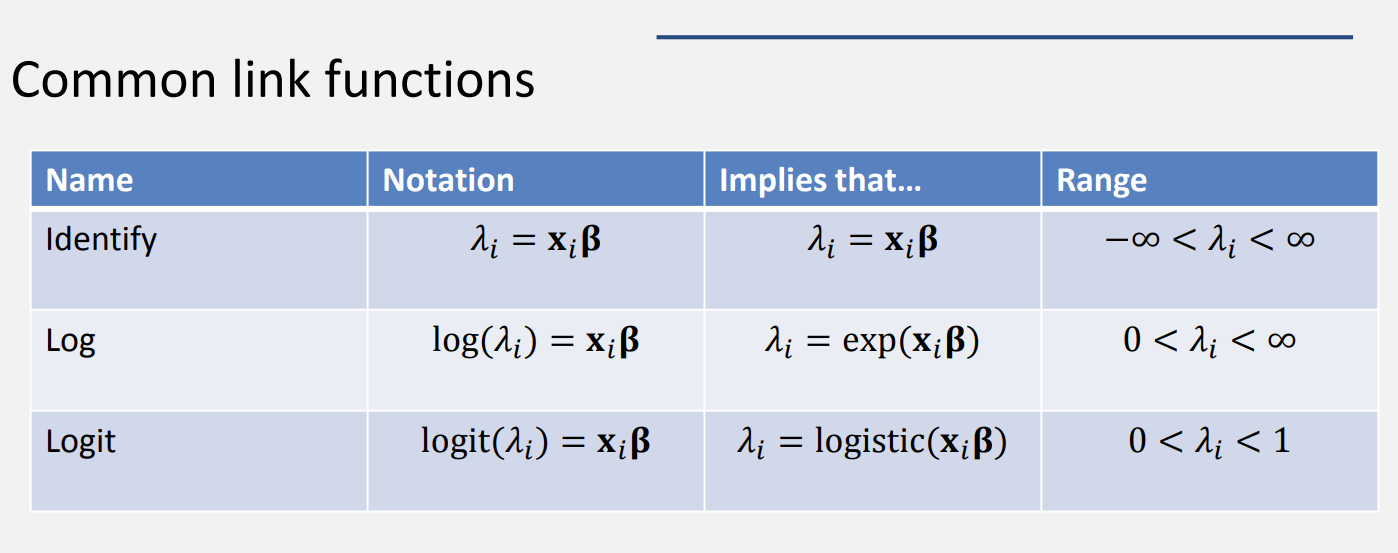

- Linear effect of covariates is expressed not for the expected response directly, but rather for a transformation of the expected response (McCullagh and Nelder 1989)

- Unifies various statistical methods, and thus fundamental to much contemporary statistical modeling

Hilbe et al. 2017; Gelman and Hill 2007; Kery and Royle 2016

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

- The linear effect of covariates is expressed not for the expected response directly, but for a transformation of the expected response (Kery and Royle 2016)

- This transformation is called a link function

We generally describe a GLM for a response \(y_{i}\) in terms of three things:

- A random component (i.e., the likelihood)

- A link function (i.e., a mathematical transformation)

- Systematic component (i.e., the linear predictor)

Hilbe et al. 2017; Gelman and Hill 2007; Kery and Royle 2016

The three parts of a GLM

- Random component of the response: a statistical distribution \(f\) with parameter(s) \(\theta\):

\[ y_{i} \sim f(\theta) \]

- A link function \(g\), which is applied to the expected response \(E(y) = \mu_{i}\), with \(\eta_{i}\) known as the linear predictor:

\[ g(E(y)) = g(\mu_{i}) = \eta_{i} \]

- Systematic part of the response (mean structure of the model containing a linear model):

\[ \eta_{i} = \beta_{0} + \beta_{1} \cdot x_{i} \]

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016

We can combine elements 2 and 3 and define a GLM succinctly as:

\[ \begin{array}{l} y_{i} \sim f(\theta) \\ g(\mu_{i}) = \beta_{0} + \beta_{1} \cdot x_{i} \\ \end{array} \]

- A response \(y\) follows a distribution \(f\) with parameter(s) \(\theta\), and a transformation \(g\) of the expected response, which is modeled as a linear function of covariates

- This is how we will code them in Stan, which makes the Bayesian framework powerful for learning GLMs

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016

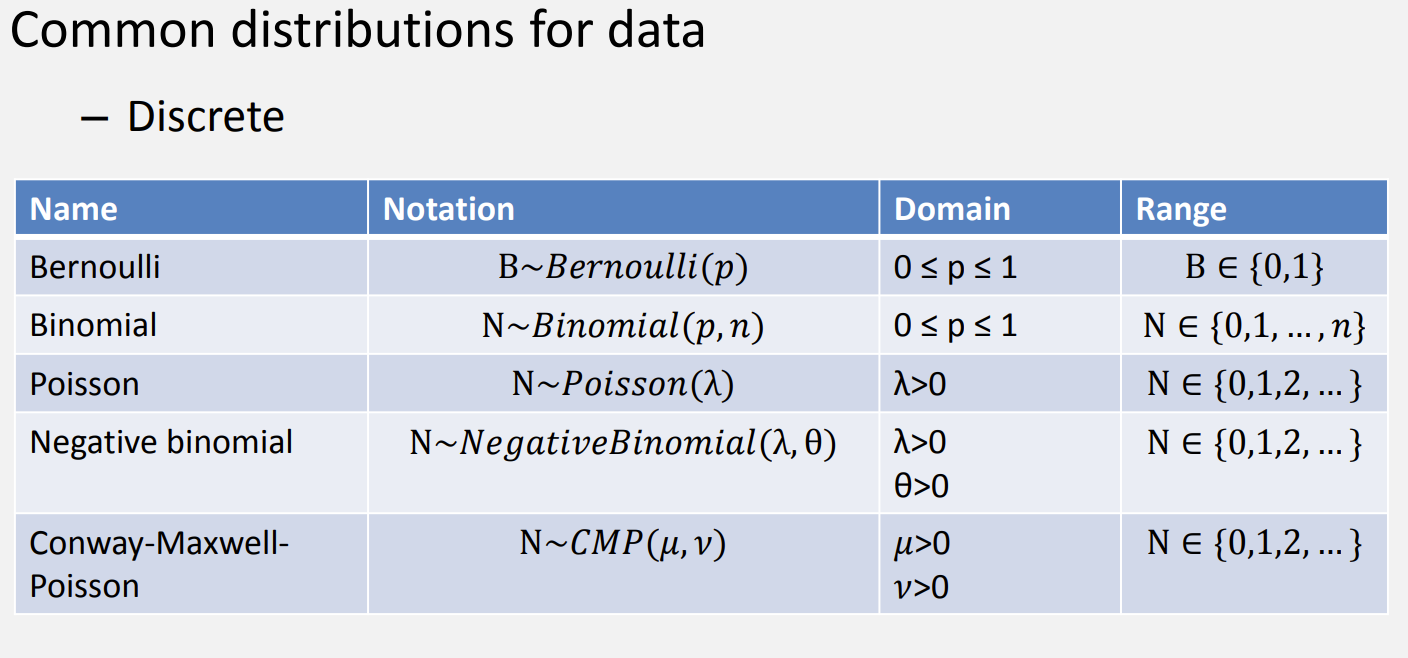

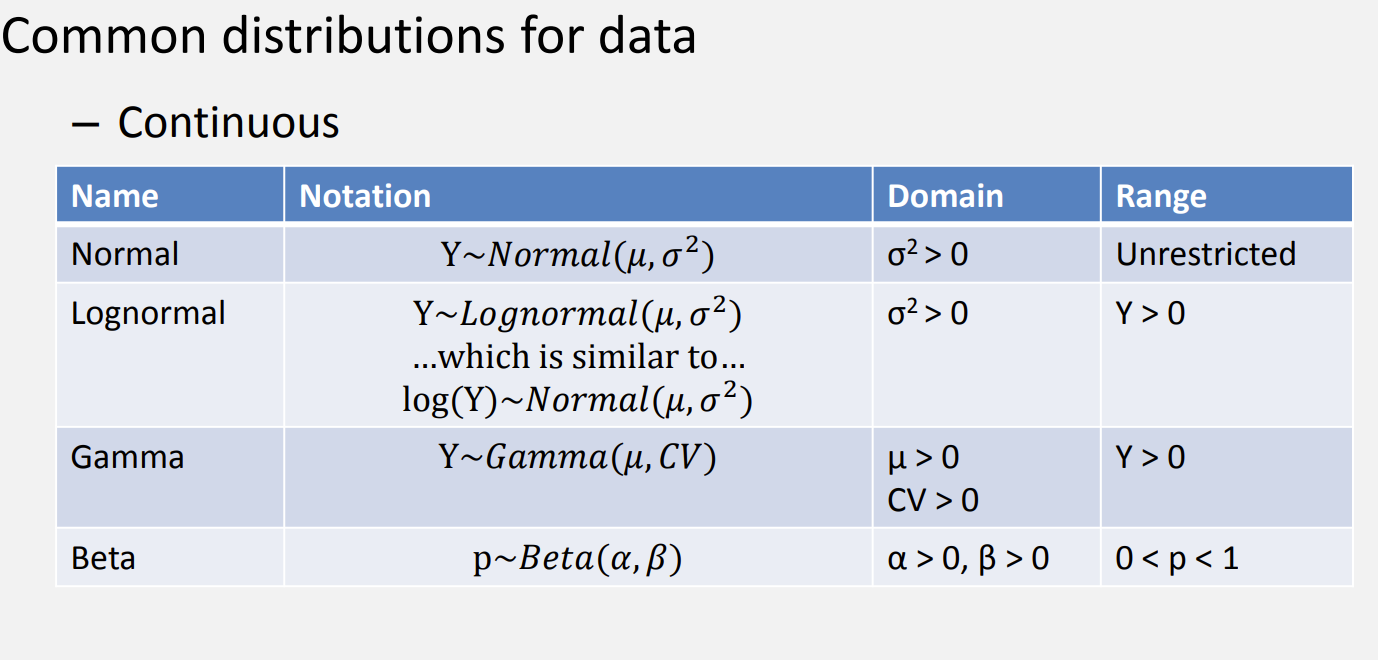

Thinking about distributions

Thinking about distributions

Justin Bois’ Distribution explorer

Thinking about link functions

Why you should care part I

- GLM concept gives you considerable creative freedom in combining the three components

- However, there are typically pairs of response distributions and link functions that go well together

- These are called canonical link functions

- Identity link for normal responses

- Log link for Poisson responses

- Logit link for binomial or Bernoulli responses

- However, there are typically pairs of response distributions and link functions that go well together

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016

Why you should care part II

- Bernoulli/binomial: survival, maturity, presence/absence, data either 0 or 1

- Poisson: abundance, recruitment, unbounded counts [0, Inf]

- Many exciting ecological models can be viewed as coupled GLMs

- GLMs are defined for all members of statistical distributions belonging to the so-called “exponential family” (McCullagh and Nelder 1989; Dobson and Barnett 2008)

- normal, Poisson, binomial/Bernoulli, multinomial, beta, gamma, lognormal, exponential, and Dirichlet

- Principles of linear modeling can be carried over to models other than normal linear regression 😎

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016

The Poisson GLM for unbounded counts

\[ \begin{array}{c} C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Poisson}\left(\lambda_{i}\right) \\ \log \left(\lambda_{i}\right)=X_{i,j} \cdot \mathbf{\beta_{j}} \end{array} \]

\(C\) is count of observation \(i\), \(X_{i,j}\) is a design matrix, \(j\) is number of columns, \(\mathbf{\beta}_{j}\) is a vector of parameters

simulate Poisson data in R:

[1] 12 20 19 16 9 16 17 17 13 20 16 12 13 13 15 11 18 17 18 18 15 7 16 19 12

[26] 13 16 20 14 16 14 9 18 13 19 13 21 17 13 11 12 8 17 14 18 16 12 11 20 22

[51] 13 10 10 24 14 17 15 12 9 20 15 23 16 12 14 17 19 15 14 11 12 19 17 14 13

[76] 13 18 13 19 17 20 11 19 17 21 17 10 15 18 18 11 11 10 21 17 18 16 21 12 15The Poisson GLM for unbounded counts

\[ \begin{array}{c} C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Poisson}\left(\lambda_{i}\right) \\ \log \left(\lambda_{i}\right)=X_{i,j} \cdot \mathbf{\beta_{j}} \end{array} \]

\(C\) is count of observation \(i\), \(X_{i,j}\) is a design matrix, \(j\) is number of columns, \(\mathbf{\beta}_{j}\) is a vector of parameters

log-probability mass of Poisson count data in R:

The Poisson GLM for unbounded counts

\[ \begin{array}{c} C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Poisson}\left(\lambda_{i}\right) \\ \log \left(\lambda_{i}\right)=X_{i,j} \cdot \mathbf{\beta_{j}} \end{array} \]

- Assumptions

- The mean and variance of the Poisson distribution are equal

- Almost never holds and usually requires a negative binomial or another model structure

- Causes of over/under dispersion are complex

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016; Zuur et al. 2017

Testing for over- or under-dispersion: Poisson GLM

- mean = variance = \(\lambda\)

- Another way: Bayesian p-value

- Idea: define a test statistic and compare the posterior distribution of that statistic for the original data to the posterior distribution of that test statistic for “replicate” datasets

- Note we could also use graphical posterior predictive checks

Gelman et al. 2006; see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016; Zuur et al. 2017

Bayesian p-value

- Pearson residuals:

\[ D\left(y_{i}, \theta\right)=\frac{\left(y_{i}-\mathrm{E}\left(y_{i}\right)\right)}{\sqrt{\operatorname{Var}\left(y_{i}\right)}} . \]

- Begin by calculating the sum of squared residuals (our test statistic) for the observed data:

\[ T(\mathbf{y}, \theta)=\sum_{i} D\left(y_{i}, \theta\right)^{2} \]

Bayesian p-value

- Next, we calculate the same statistic for replicate (simulated) datasets

\[ T\left(\mathbf{y}^{\text {new }}, \theta\right)=\sum_{i} D\left(y_{i}^{\text {new }}, \theta\right)^{2} \]

- Bayesian p-value is simply the posterior probability \(\operatorname{Pr}\left(T\left(\mathbf{y}^{\text {new }}\right)>T(\mathbf{y})\right)\)

- Should be close to 0.5 for a good model, too near 0 or 1 indicates lack of fit (somewhat subjective)

see Chapter 3, Kery and Royle 2016; Zuur et al. 2017

The binomial GLM for bounded counts or proportions

- Often have counts bounded by an upper limit

- Number of successful breeding pairs cannot be higher than all observed breeding pairs

- Proportion of nestlings surviving

- These types of data require the binomial GLM

Kery and Schaub 2012

The binomial GLM for bounded counts or proportions

- Random part of the response (statistical distribution)

\[ C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Binomial}\left(N_{i}, p_{i}\right) \]

- Link of the random and systematic bit (logit link):

\[ \operatorname{logit}\left(p_{i}\right)=\log \left(\frac{p_{i}}{1-p_{i}}\right)=\eta_{i} \]

- Systematic part (linear predictor):

\[ \eta_{i}=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}{ }^{*} X_{i}+\beta_{2}{ }^{*} X_{i}^{2} \]

The binomial GLM for bounded counts or proportions

\[ C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Binomial}\left(N_{i}, p_{i}\right) \]

\[ \operatorname{logit}\left(p_{i}\right)=\log \left(\frac{p_{i}}{1-p_{i}}\right)=\eta_{i} \]

\[ \eta_{i}=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}{ }^{*} X_{i}+\beta_{2}{ }^{*} X_{i}^{2} \]

where \(p_{i}\) is expected proportion on arithmetic scale and is mean response of each of the observed \(N_{i}\) trials

\(\eta_{i}\) is the same proportion but on the logit-link scale

The binomial GLM for bounded counts or proportions

\[ \operatorname{logit}\left(p_{i}\right)=\log \left(\frac{p_{i}}{1-p_{i}}\right)=\eta_{i} \]

- Logit maps the probability scale (i.e., range 0 to 1) to the entire real line (i.e., -\(\infty\) to \(\infty\))

- The rest of the model (linear predictor) is up to you, your data, your questions, and your imagination

Kery and Schaub 2012

Overdispersion and underdispersion in the binomial distribution

- Note that the binomial distribution variance is equal to

\[ N \cdot p \cdot (1-p) \]

- Need to check the binomial for under and over dispersion similar to how we check for the Poisson

- See this paper for some useful logistic regression checks

In-class exercise

In-class exercise

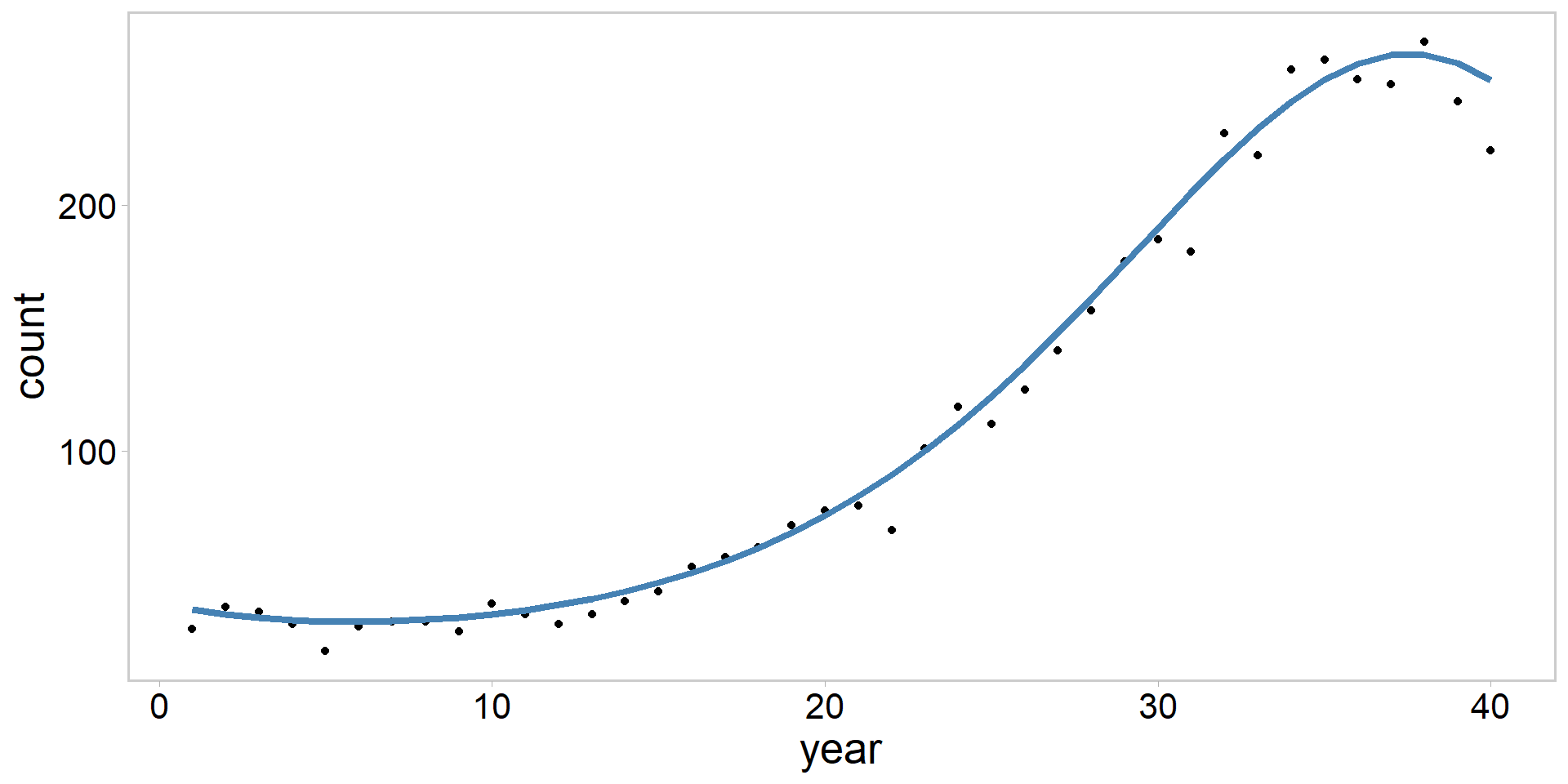

- Let’s simulate a Poisson GLM, where we model peninsular homing clam 🥟 counts as a function of year:

\[ \begin{array}{c} C_{i} \sim \operatorname{Poisson}\left(\lambda_{i}\right) \\ \log \left(\lambda_{i}\right)=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1} \cdot \operatorname{year}_{i} +\beta_{2} \cdot \operatorname{year}_{i}^2 + \beta_{3} \cdot \operatorname{year}_{i}^3 \end{array} \]

- Clam counts follow a cubic polynomial function of time

- Note this equation is still linear in the predictors

- Where do we begin?

Kery and Schaub 2012

Peninsular homing clams 🥟: simulating fake data

- Let’s get it started (in here)

- Exercise: see if you can generate fake data for this model

- Start by calculating the systematic component, then apply the link function, and lastly generate random deviates according to the Poisson distribution

Homing clam simulation solution 🥟

Coding the 🥟 model in Stan

- Assume Normal(0, 10) priors for everything

- Should look similar to the simulation code

- Hint: you will get a funny error message and we will work through it as a group

Writing the clams.stan file 🥟

- Work together to get this model estimating

Go to solution files

Summary and Recap

- We have covered much ground

- Statistical models as response = deterministic + random

- ANCOVA

- Introduced GLMs, which allow us to model data coming from distributions other than the normal

- Examined Poisson and Binomial GLMs

- Talked about dispersion

- This material lays the foundation for more complicated models

References

- Gelman et al. 2015. Stan: A probabilistic programming language for Bayesian inference and optimization

- Gelman et al. 2006. Bayesian Data Analysis.

- Gelman and Hill 2007. Data analysis using regression and multilevel models

- Hilbe et al. 2017. Bayesian models for Astrophysical data

- Kery 2010. Introduction to WinBUGS for ecologists

- Kery and Royle 2016. Applied hierarchical modeling in ecology

- Kery and Schaub. 2012. Bayesian Population Analysis using WinBUGS. Chapter 3

- McCullagh and Nelder 1989. Binary data. In Generalized linear models (pp. 98-148). London: Chapman and Hall. 511 pp

- Zuur et al. 2017. Beginner’s Guide to spatial, temporal, and spatial-temporal ecological data analysis with R-INLA. Highland Statistics Ltd.