1-02: Variables

0.1 Changes

1 Purpose

Discuss what a programming variable is and how it compares to an algebraic variable.

Discuss naming conventions for variables.

Assign and reassign values to variables

Introduce in-line and whole-line comments.

2 Questions about the material…

If you have any questions about the material in this lesson, feel free to email them to the instructor, Charlie Belinsky, at belinsky@msu.edu.

3 Programming structures

In all programming languages there are 4 main structures that cover almost every aspect of programming:

Variables: named storage area for values used in the script

If-Else Statements: conditional execution of code

For Loops: execution of code a fixed number of times

Functions: place to store commonly used code

We will go through all 4 of these in the class and in the lesson we will cover the first, Variables.

4 Different types of variables

Variables is a widely used term found in many different fields, and its definition is not consistent across the fields. In this class, when I say variable I am referring to a programming variable. When I am referring to a variable in another field, I will add the field to the term variable (e.g., algebraic variable, experimental variable, statistical variable).

4.1 Algebraic variables

In Physics, we use algebraic variables to describe the relationship between physical properties. For example, velocity can be expressed algebraically as v=d/t where v, d, and t are symbols representing the physical properties of velocity, distance, and time. The formula states that the relationship v=d/t is always maintained even as the individual values change.

In this case, v, d, and t are all algebraic variables that have the following properties:

Name: v, d, t (name is synonymous with symbol)

Type: numeric (v, d, and t are all numbers)

Value: given by situation – the value can be known or unknown

4.2 Variables in programming

In programming, variables work in a similar way. Variables in programming are named storage locations in memory that hold information.

This information could be

a runner’s distance, time, and velocity

the number of fish caught in a day

the name of the lake the fish were caught in

weather information such as temperature, humidity, or wind speed

Like algebraic variables, variables in programming have a name, type, and value.

4.2.1 Name

The name corresponds to the symbol in our physics example above – it is how the variable is represented in the script. The name is used to reference the storage location in memory that holds the value. For our initial example, we will use v, d, and t as the variable names. Later in this lesson, I will talk about variable naming conventions.

4.2.2 Value

The value is the information that is stored in the location pointed to by the name, so when v = 10 , that means there is a storage location in memory named v, and in that location, there is the number 10. Note: we will worry about units later.

4.2.3 Type

The type describes what kind of value is being stored in memory which, in turn, tells R what kind of operations can be performed on the variable. Distance, velocity, and time all have numeric values, and mathematical operations can be performed on them.

Numeric is one type of value a variable can have, some of the other types of values are:

strings (also called characters): a text value (e.g., a lake name)

categorical: a limited set of text values (e.g., the four seasons or the five Great Lakes)

Boolean: a TRUE/FALSE statement

Date: a date in day-month-year format

We will talk more about the non-numeric variable types in future lessons, for now, we will stick with numeric variables.

5 Using variables in a script

We are going to create a simple script that calculates velocity given distance and time.

There are three variables in this script: d, v, and t

The steps for making this script are:

Open Your RStudio Project (or create one if you do not have one)

Create a new script file

Add code to the script

Execute (Source) the code

5.1 Open your RStudio Project

It would be best to use the same RStudio Project for the whole class and you can use the one you created in the last lesson.

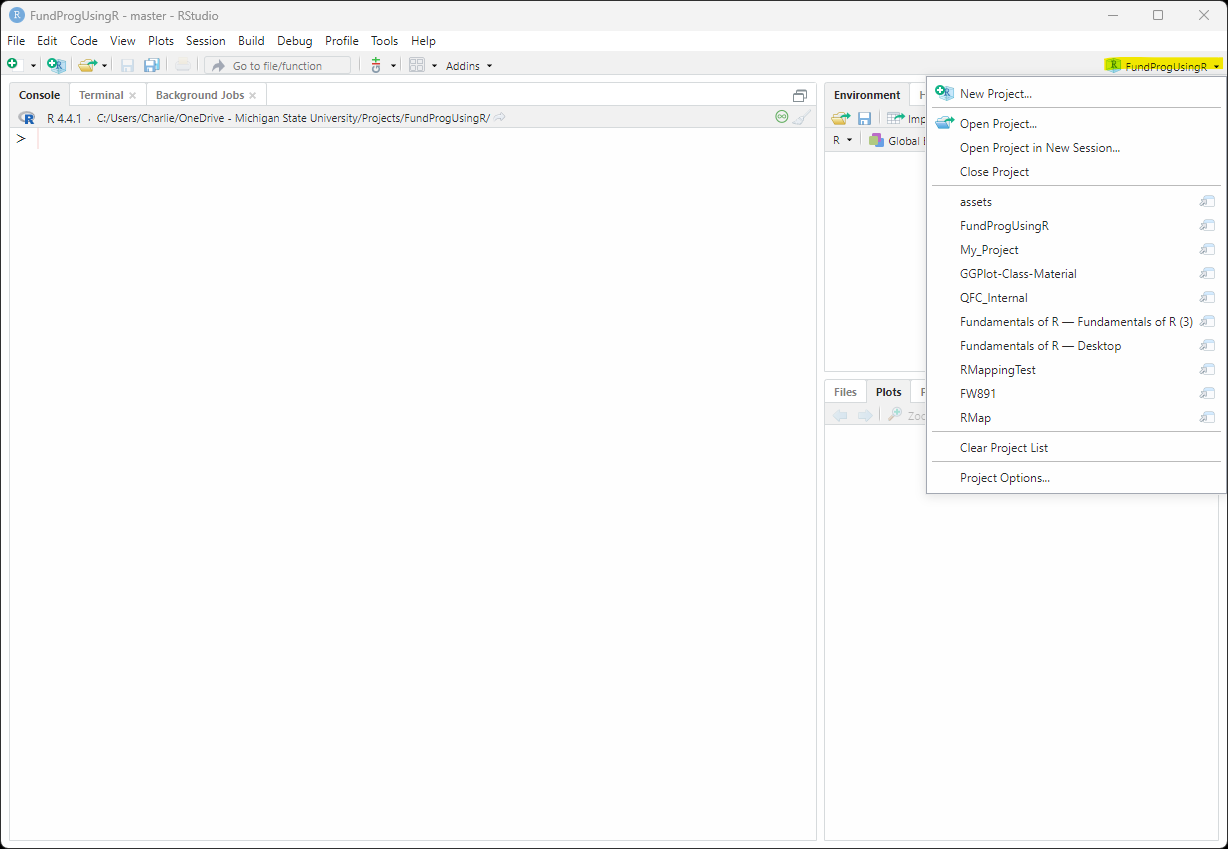

There are multiple ways to open an RStudio Project:

Open your Project Folder in a file manager and double-click the *.proj file, where * is the name of your project

In RStudio, click File -> Open Project… -> navigate to your Project Folder and click the *.proj file

In RStudio, click File -> Recent Projects -> choose the RStudio Project

(The method I find most useful) Use the Projects dropdown menu in the top-right corner of RStudio (Figure 1)

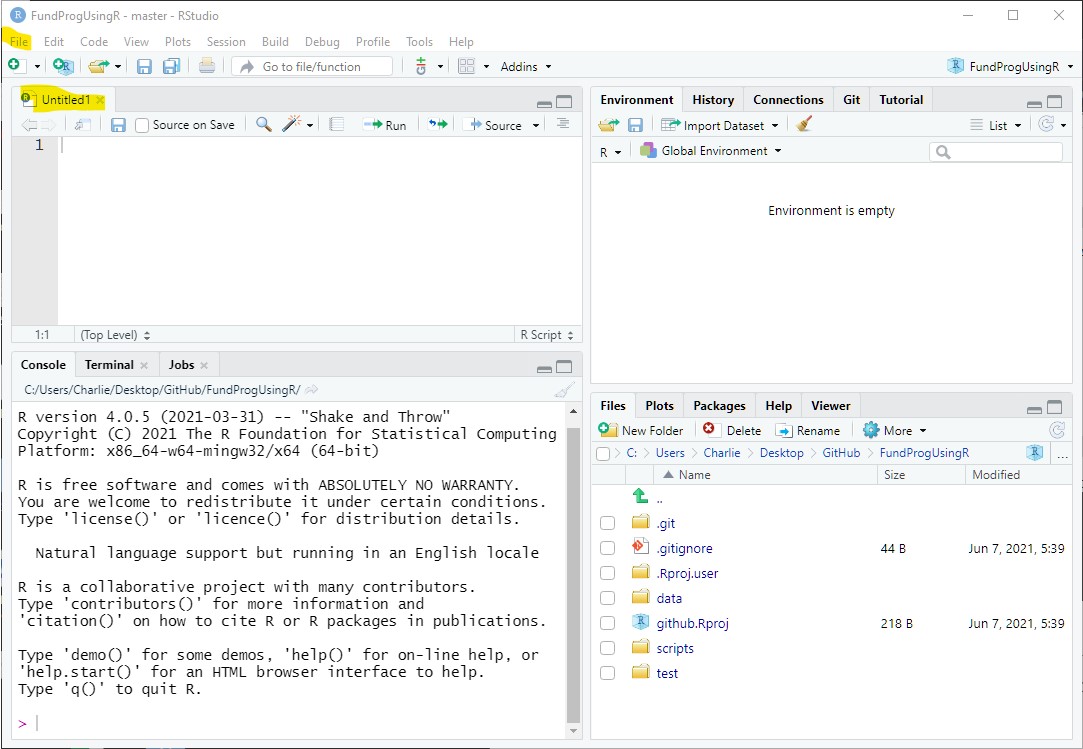

5.2 Open a new script file

Inside your RStudio Project, click on File -> New File -> R Script (Figure 2) . An empty file named Untitled1 will appear as a tab in the File Editor window. Save the file as lesson1-02.r in your script folder.

Note: you should always name and save a script file before editing it. Do not leave it as Untitled1

5.3 Add code to the script

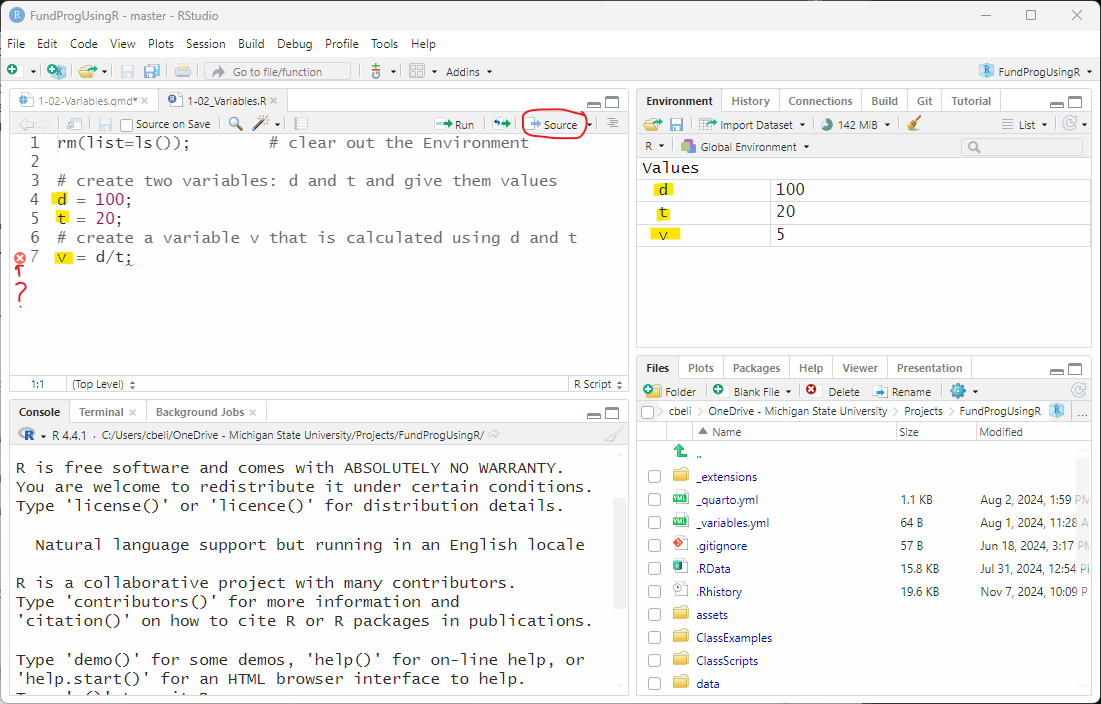

Copy and paste the following lines into the code window and click the Source button in the bar above the code (or click Code -> Source):

rm(list=ls()); # Clear out the Environment

# create two variables: d and t and give them values

d = 100;

t = 20;

# create a variable v that is calculated using d and t

v = d/t;Lines 1 cleans out the Environment tab (top-right corner) each time the script is executed. This provides you with a clean slate each time you run a script and I put this line at the top of most of my scripts.

Extension: Why clear the Environment tab?

Line 1 also has an inline comment that starts with #. Everything after the # is informational and does not get executed.

Lines 3 and 6 are full comment lines – again, they are informational and there to make the script easier to understand. You can take them out and the script will produce the same result.

Lines 4, 5, and 7 are where the real action occurs and each line contains a variable assignment:

Line 4 assigns the value 100 to the variable named d

Line 5 assigns the value 20 to the variable named t

Line 7 assigns the value of the calculation d/t to the variable named v.

Lines 1, 4, 5, and 7 all have semicolons ( ; ) at the end. The semicolon designates the end of a programming command just like the period designates the end of a sentence. The semicolon is optional in R and is often not used, but I highly recommend the use of semicolons in all of your scripts. Semicolons allow for more flexibility (e.g., you can put multiple commands/“sentences” on one line), help you think about the flow of your code, and are required in many programming languages.

5.4 Execute your code – the Environment tab

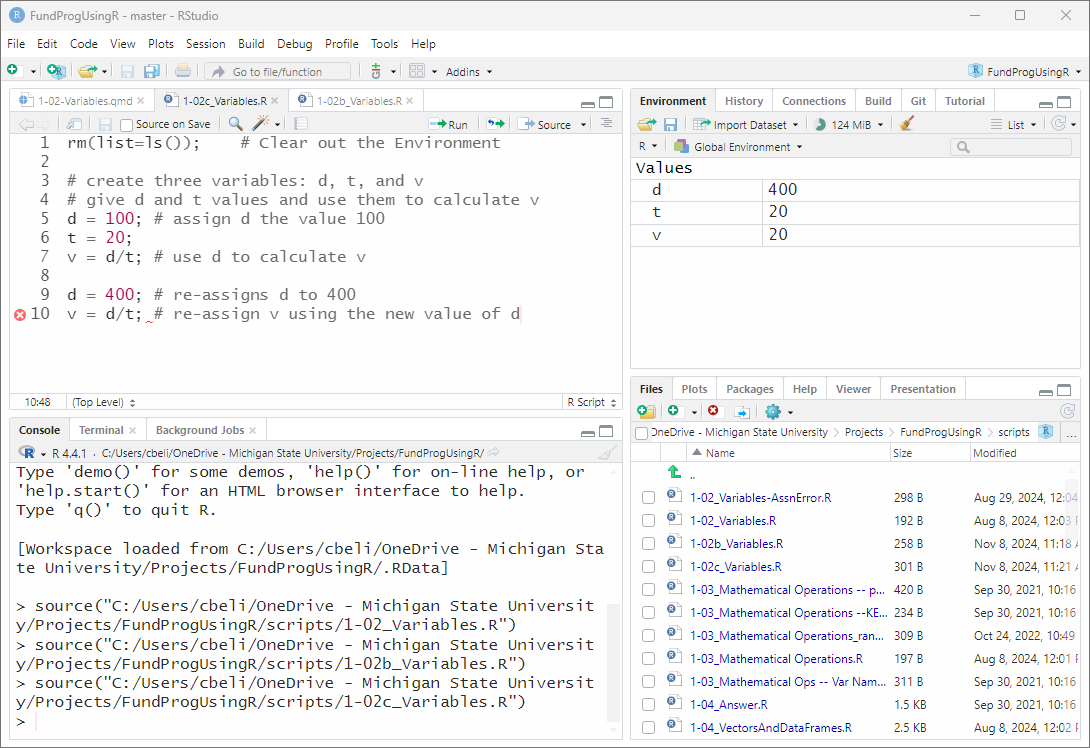

Click Source to execute your R code ( Figure 3 ). Your RStudio window should look similar to this:

Notice that the Environment tab displays the values for the variables v, d, and t. The Environment tab displays every variable in your script and is a very useful tool for viewing the results of your script and for debugging when things go wrong..

Try changing the values for d and t (lines 7 and 8) and click Source again to see how the values in the Environment tab change.

5.4.1 The Unexpected end of document error

In Figure 3 there is a red x on the last line indicating an error. The error says unexpected end of document. This is not a real problem, it will not cause any issues with your script. It is a bug in how RStudio deals with semicolons. You can remove the last semicolon if you want to get rid of the error.

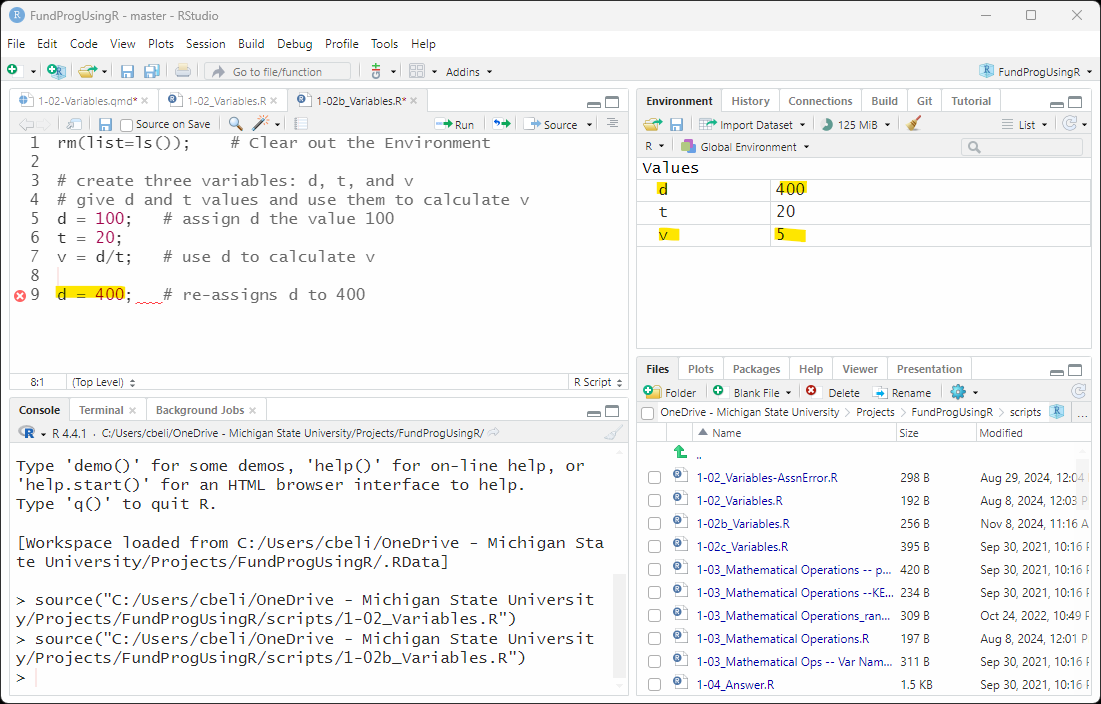

6 Re-assigning values to variables

Variables get their namesake from the fact that their values can change.

In the code below:

d is assigned the value 100 in line 5

d to used to calculate v in line 7

d is assigned a new value of 400 in line 8

Source the code below to see what happens

rm(list=ls()); # Clear out the Environment

# create three variables: d, t, and v

# give d and t values and use them to calculate v

d = 100; # assign d the value 100

t = 20;

v = d/t; # use d to calculate v

d = 400; # re-assigns d to 400In the Environment tab the value of v remains 5 even though d changes.

The value of v remains 5 because line 7 assigns the current value of d/t to v. But, as of line 9, d is still equal to 100. v does not get updated because one of the variables used to calculate it (in this case, d) changes afterwards. The script runs in order, and variables are not updated retroactively.

In other words, v will remain 5 until it is explicitly assigned another value.

Trap: Assigning nonexistent variables

6.1 Reassigning values to a variable

What happens if you add the line v=d/t at the end of the script? Try the following code and click Source

rm(list=ls()); # Clear out the Environment

# create three variables: d, t, and v

# give d and t values and use them to calculate v

d = 100; # assign d the value 100

t = 20;

v = d/t; # use d to calculate v

d = 400; # re-assigns d to 400

v = d/t; # re-assign v using the new value of dNotice that now the value of v has changed. This is because line 10 assigns a new value to v calculated using the value of d from line 9.

7 In-line and whole-line comments

The code in the previous script (Figure 5) has examples of whole-line comments (lines 3 and 4) and in-line comments (lines 5, 7, 9, and 10 ). R ignores everything after the ( # ) but still executes everything on the line before the ( # ). In-line comments are a nice way to give a quick description of the code on a line, whereas whole-line comments are better for more robust descriptions – especially when code get complicated.

8 Naming variables

The problem with variable names like v, d, and t is that they are not very descriptive. It is good programming practice to give names that are descriptive so that people reading your code can more easily understand what is going on.

The first step would be to spell the variable names out, for example: velocity, distance, and time.

However, a script solving for velocity will probably be calculating multiple velocities. Perhaps the script is calculating the velocity of both a runner and a car – the variable names should reflect this.

8.1 Naming Rules

There are a few rules for naming a variable:

It must start with a letter

It can only contain letters, numbers, or the underscore ( _ )

- dots ( . ) are also accepted in R but dots are not accepted in most programming languages

- this means no spaces!

There are system reserved words you cannot use as variable names (e.g., if, else, for, while, TRUE, FALSE, function, next…). We will learn what these reserved words mean in future lessons.

8.2 Naming Conventions

There are two common programming conventions for variables names:

Capitalize the first letter of every word except the first: runnerVelocity, runnerDistance, runnerTime

Put an underscore ( _ ) between each word: runner_velocity, runner_distance, runner_time

Trap: Case counts in variable names

For all your class work, you need to use these two conventions. I will use the first convention in most of my examples.

Note: R programmers often use dots in variable names: runner.velocity, runner.distance. I do not recommend this as this method will not work in most other programming languages.

9 Application

Two runners run a 400 meter race.

The first runner takes 127 seconds, the second runner takes 140 seconds.

Write a script that:

Calculates each runner’s speed in meters/second

Calculates each runner’s speed in miles/hour

3600 seconds = 1 hour

1609 meters = 1 mile

So, the script will calculate 4 velocities in all.

Make sure you use variables for all values and follow proper variable naming convention.

After your Source the script, make sure you can see all of the variables, with the correct answer, in the Environment tab.

Save the script as app1-02.r in your scripts folder and email your Project Folder to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

Instructions for zipping the Project Folder are here.

If you have any questions regarding this application, feel free to email them to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

9.1 Questions to answer

Answer the following in comments inside your application script:

What was your level of comfort with the lesson/application?

What areas of the lesson/application confused or still confuses you?

What are some things you would like to know more about that is related to, but not covered in, this lesson?

9.2 Challenge

This challenge is only for those who have some programming experience already.

Use random values for the times instead of 127 and 140. The easiest way to get a random number in R is to use the sample() function:

Examples:

randomNum1 = sample(x=10:20, size=1); # number between 10 and 20 (inclusive)

randomNum2 = sample(x=-5:5, size=1); # number between -5 and 5 (inclusive)10 Trap: Assignment vs. Equality Operations

The equal sign ( = ) plays a different role in programming than in Algebra.

In algebra, the equal sign is an equality operator saying that the two sides are equivalent to each other.

So, in algebra, v = d/t says that v is equivalent to d divided by t

The algebraic variable v will change if d or t changes

In programming, the equals sign is an assignment operator and it says that the variable on the left side will be assigned the value calculated on the right side.

So, in programming, v = d/t says that v will be assigned the calculation of d divided by t

In this case, v will not change if d or t changes (unless v is explicitly reassigned after d or t changes). Once assigned, the value of v is independent of the variables used in the calculations.

10.1 Treating the equal sign as an equality operation

A very common error in programming is to treat the assignment operator ( = ) as an equality operator.

The following statements make sense in algebra as equality statements but will cause errors in R.

# d/2 is not a valid variable, you cannot "assign" a value to "d/2"

# d = 100*2 is valid

d/2 = 100;

# 20 cannot be assigned the value of 't'

# t = 20 is valid

20 = t;

# d/t is not a valid variable

# v = d/t is valid

d/t = v;Put the above lines of code in your script individually and note the, often unintutive, error message that gets displayed in the Console tab.

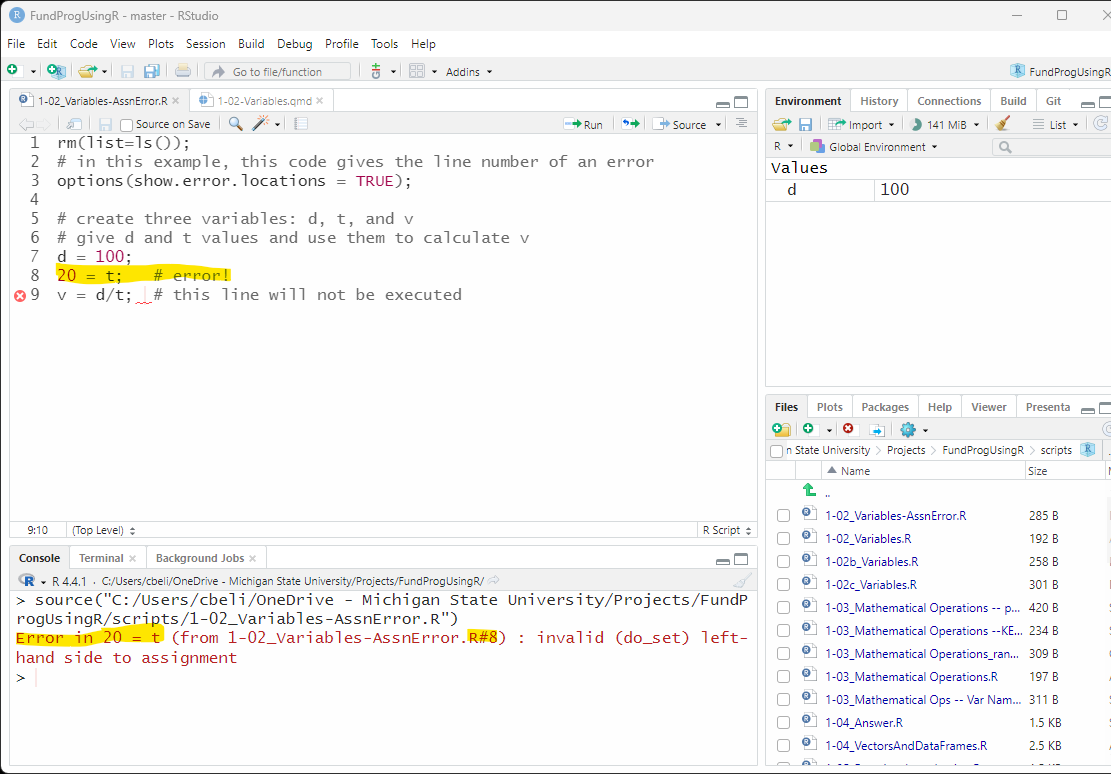

In the following example (Figure 6), line 9 contains an error and the lines below it never gets executed:

rm(list=ls());

# this code sometimes gives the line number of an error

options(show.error.locations = TRUE);

# create three variables: d, t, and v

# give d and t values and use them to calculate v

d = 100;

20 = t; # error!

v = d/t; # this line will not be executed

Notice that the execution of the script stops as soon as an error occurs – so, in this case, line 9, which calculates v, never gets executed.

11 Trap: Constant variables in R

There are mathematical constants like π that should never change, and R has a predefined variable named pi that is equal to 3.1415. In other words, there is a storage location in R referred to as pi that contains the numeric value 3.1415. The problem is that pi is technically a variable in R and can be changed.

Source the following code in a new script file:

rm(list=ls());

a = pi; # pi is a predefined constant in R

pi = 3; # But, R let's you reassign a value to pi

b = pi; # And now there is going to be a problemAnd you will see that you can reassign the value of pi in R. Most programming languages will give an error if you try to do this.

12 Trap: Assigning nonexistent variables

The first time you assign a value to a variable, a storage container is created in memory and a value is put in it. We call this a declaration (more about declarations later). After a variable has been declared, it can be used in calculations and reassigned values. Before a variable is declared, R knows nothing about the variable.

Here is an example of using a variable before it is declared. Note: the only change in this script was moving the line v=d/t before the declaration of d and t:

rm(list=ls());

# gives the line number of the error

options(show.error.locations = TRUE);

# create three variables: d, t, and v

# give d and t values and use them to calculate v

v = d/t; # error, d and t have not been declared

d = 100;

t = 20;If you Source this code in a new script file, you will get an error in the Console tab that says object ‘d’ not found. The reason for this error is that, on line 7, the script is asked to assign the calculation d/t to the variable v but d and t do not exist yet.

Try the following code and see how the error changes. Notice in this code v=d/t is after the declaration of d but before the declaration of t.

rm(list=ls());

# gives the line number of the error

options(show.error.locations = TRUE);

# create three variables: d, t, and v

# give d and t values and use them to calculate v

d = 100;

v = d/t; # error

t = 20;13 Trap: Case counts in variable names

In R, as in most scripting languages, uppercase and lowercase letters are seen as different. So, runnersTime and runnerstime are seen by R as two different variable names. If the case is not correct, then you will receive an Object not found error just like you would if you tried to use a variable that does not exist.

14 Extension: alternate assignment operator

In R, there are two assignment operators, the equal sign ( = ) and the arrow ( <- ).

rm(list=ls()); # Clear out the Environment

d <- 100; # same as d = 100

t <- 20; # same as t = 20

v <- d/t; # same = d/tYou will see a lot of R programs written using the arrow. In this class, I will use the equal sign because that is the standard for most other programming languages (including JavaScript and C) and it is easier to type. You can use either operator in your scripts in this class.

For assigning values to a variable, ( <- ) and ( = ) are functionally equivalent. There is a difference between the two operators when working with functions, which we will cover in a later lesson.

15 Extension: Why clear the Environment tab?

There are many people who come to this class having already done some R programming and it is most likely they never clear the Environment when running scripts. This means that variables are persistent and will still be around when another script is executed.

This, in general, is a bad programming practice, which I will talk more about in future lessons. If a script needs a variable from another script then you want the first script to call the second script. This kind of explicit programming makes sharing and debugging your scripts a lot easier.