1-09: If-Else Statements

0.1 Issues

1 Purpose

Create condition statements that control flow for either TRUE or FALSE conditions using an if-else structure

perform multiple conditional statements on one variable using an if-else-if structure

create error conditions in an if-else-if structure with an else statement

2 Questions about the material…

The files for this lesson:

Script: you can download the script here

If you have any questions about the material in this lesson, feel free to email them to the instructor, Charlie Belinsky, at belinsky@msu.edu.

3 Dealing with FALSE conditions

In the last lesson we looked at execution of the if() statement and how it changes the flow of a script. if() statements contain a conditional statement inside the parenthesis and an attached codeblock surrounded by curly brackets ( { } ). The codeblock is only executed if the conditional statement is TRUE.

randomNum = sample(1:100, size=1);

if(randomNum > 50) # execute the attached codeblock if TRUE

{

cat("You win");

}3.1 else and FALSE conditions

Many times when you are programming you want to execute something when the condition (e.g., temperature > 50) is TRUE and something different when the condition is FALSE.

You can execute a codeblock on a FALSE condition by using an if-else statement:

randomNum2 = sample(1:100, size=1);

if(randomNum2 > 50) # execute the attached codeblock if TRUE

{

cat("You win");

}else # execute this codeblock if FALSE

{

cat("You lose");

}If the condition is TRUE, the codeblock in the curly brackets ( { } ) attached to the if() gets executed.

If the condition is FALSE, the codeblock in the curly brackets attached to the else gets executed.

Note: Like if() statements, if-else statements are often used within for loops to check multiple values at once (e.g., all values in a column of a data frame) – we will be getting to that in the next lesson.

3.2 Curly bracket placement in R and a bug

Figure 1 uses the bracket placement I prefer. However, when you see an R script you often see people write their if-else statements like this:

if(randomNum2 > 50) {

cat("You win");

} else {

cat("You lose");

}I find the method in Figure 2 harder to read and more challenging to add comments to than the method in Figure 1. However, for this class, you can use either method when coding if-else structures.

Note: Neither method follows programming standards that you will find in most other language. More information about this is here: Extension: Programming standards for if-else statements

4 if-else statements and conditional operators

Let’s now look at the script for the lesson. Like last lesson, we:

read in the data from twoWeekWeatherData.csv

save the highTemp and noonCondition column to a vector

### read in data from twoWeekWeatherData.csv

weatherData = read.csv(file="data/twoWeekWeatherData.csv",

sep=",",

header=TRUE);

### Extract the highTemps column from the data frame -- save it to a variable

highTemps = weatherData$highTemp;

noonCond = weatherData$noonCondition;This time, the script executes a codeblock for both TRUE and FALSE conditions:

if(highTemps[3] > 50)

{

cat(" high temp 3 is greater than 50\n");

}else # highTemp[3] <= 50

{

cat(" high temp 3 is not greater than 50\n");

}

if(highTemps[4] > 50)

{

cat(" high temp 4 is greater than 50\n");

}else

{

cat(" high temp 4 is not greater than 50\n");

}

if(highTemps[5] > 50)

{

cat(" high temp 5 is greater than 50\n");

}else

{

cat(" high temp 5 is not greater than 50\n");

}Now the script outputs information for all three highTemp values, two of which were less than 50

Checking highTemps 3, 4, and 5 to see which are > 50:

high temp 3 is greater than 50

high temp 4 is not greater than 50

high temp 5 is not greater than 505 If-Else statements using strings

Conditional operators can also be used to compare two string values. Usually, we are using == or != to compare string values. So, the else statement can be used for the opposite condition:

if(noonCond[2] == "Cloudy") # noonCond[2] is "Cloudy"

{

cat(" Day was Cloudy\n");

}else # noonCond[2] is not "Cloudy"

{

cat(" Day was not Cloudy\n");

}

if(noonCond[3] != "Sunny") # noonCond[3] is not "Sunny"

{

cat(" Day was not Sunny\n")

}else # noonCond[3] is "Sunny"

{

cat(" Day was Sunny\n")

}Day 2 was cloudy (the if condition) and day 3 was sunny (the else condition)

Check to see the noon condition on the day 2:

Day was Cloudy

Day was Sunny5.1 if-else vs. if() statements

You could just write the code in Figure 4 using only if statements and the code would output the same messages:

if(noonCond[2] == "Cloudy") # noonCond[2] is "Cloudy"

{

cat(" Day was Cloudy\n");

}

if(noonCond[2] != "Cloudy") # noonCond[2] != "Cloudy"

{

cat(" Day was not Cloudy\n");

}

if(noonCond[3] != "Sunny") # noonCond[3] is not "Sunny"

{

cat(" Day was not Sunny\n")

}

if(noonCond[3] == "Sunny") # noonCond[3] is "Sunny"

{

cat(" Day was Sunny\n")

}But there are two problems with the code above:

You are executing code that you know does not need to be executed. Sunny and Not Sunny are mutually exclusive – there is no need for the script to check both. This extra check adds a little bit to the script’s execution time and this can make a difference if you are checking 100,000 values in a data frame.

An if-else statement is easier to debug than two individual if() statements because you only need to debug one conditional statement – as opposed to two.

6 Adding in more conditions: if-else-if Structures

We are limited to two outcomes when using if-else structures: (a) the if() condition is TRUE or (b) The if() condition is FALSE. However, the examples above contain situations that could easily have more than two possible condition. For instance, the noonCondition can be “Sunny”, “Cloudy”, or “Rain” – and we can check for all three in an if-else-if structure.

With an if-else-if structure you can check as many mutually exclusive situations as you want.

if(noonCond[4] == "Cloudy") # 1st check: the day is cloudy

{

cat(" Day 4 was cloudy\n");

}else if(noonCond[4] == "Sunny") # 2nd check: the day is sunny

{

cat(" Day 4 was sunny\n");

}else if(noonCond[4] == "Rain") # 3rd check: the day is rainy

{

cat(" Day 4 was rainy\n");

}Checking day 4 against multiple conditions:

Day 4 was rainy 6.1 The efficiency of if-else-if structures

if-else-if structures are efficient because they quit once they find a conditional statement that is TRUE.

In Figure 6, if we replaced day 4 with day 2, which was “Cloudy”, then only the first condition (noonCond[4] == “Cloudy”) gets checked. Because “Cloudy” is TRUE there is no need to check “Sunny” and “Rain”. If there are thousands of values to check (e.g., you are checking all the values in a large vector – next lesson) then a lot of computational time is saved by not checking conditions that cannot be TRUE.

7 The error or everything else condition

We often want to execute something for values we have not prepared for. For instance, a phone system might have menu options numbered 1 through 5. If the user presses 7, the system will usually have a message saying something like “sorry, 7 is not an option”.

The problem with the script above is that it does nothing if the condition for the day is not given anywhere in the if-else-if structure (i.e., all the conditional statements are FALSE). In an if-else-if structure you cannot anticipate everything that somebody will input into a dataframe – let alone all of the errant spellings. To resolve this, we create what is often referred to as an error condition, meaning we set up a codeblock that gets executed if none of the conditions in the if-else-if structure are TRUE. This error codeblock gets attached at the end to an else statement.

if(noonCond[5] == "Cloudy") # 1st check: the day is cloudy

{

cat(" Day 5 was cloudy\n");

}else if(noonCond[5] == "Sunny") # 2nd check: the day is sunny

{

cat(" Day 5 was sunny\n");

}else if(noonCond[5] == "Rain") # 3rd check: the day is rainy

{

cat(" Day 5 was rainy\n");

}else # none of the above are TRUE so output some error message

{

cat(" The condition for day 5,", noonCond[5], ", is invalid\n");

}Since we have an else statement at the end, there is guaranteed to be a response from the script no matter what noonCond is:

Checking day 5 against multiple conditions:

The condition for day 5, Fog, is invalid7.1 Error statement help in debugging

Adding the error statement also helps you debug your code. In this case, the error statement tells you that some value (Fog) does not meet any of the conditions and you can use the codeblock attached to the else statement to provide useful information about what went wrong – and perhaps suggest a fix.

8 Creating number ranges using if-else structures

Another use for if-else-if structures is to create number ranges. The following code categorizes the highTemp by temperature range.

if(highTemps[3] > 70) # check for anything above 70

{

cat(" That is hot for April!");

}else if(highTemps[3] > 60) # check for temps 61-70

{

cat(" That is warm for April!");

}else if(highTemps[3] > 50) # check for temps 51-60

{

cat(" That temperature is about right for April!");

}else if(highTemps[3] > 40) # check for temps 41-50

{

cat(" That is a little cold for April!");

}else # temperatures 40 and below

{

cat(" That is unusually cold for April!");

}Checking temperature of day 3:

That temperature is about right for April!8.1 if-else-if statements are mutually exclusive

An if-else-if structure ends as soon as a condition is determined to be TRUE. This means that at most one codeblock in an if-else-if structure gets executed. In the above example (Figure 8), if the temperature is 75 (i.e., day 14), the first condition (highTemps[14] > 70) is TRUE and “That is hot for April” is output. The if-else-if ends here and none of the other conditions are checked.

The second condition (highTemp[14] > 60) would, if checked, also be TRUE. But this condition does not get checked because a condition above was already TRUE – the if-else-if structure is done executing.

Again, in an if-else-if structure, only the codeblock attached to the first TRUE conditional statement gets executed. If none of the conditional statements are TRUE then the codeblock attached to the else statement at the end is executed.

9 Application

A) In comments answer: Why can I say that the fourth condition else if(highTemps[3] > 40) in Figure 8 checks only for values between 41 and 50 when the condition is highTemps[3] > 40?

B) In comments answer: Why might it be easier to find errors in a dataset using if-else-if structures vs. just if() statements?

C) The following line randomly picks a letter from the vector and saves it to grade:

grade = sample(c("A", "B", "C", "D", "E"), size=1);Using the above line:

Have the script output the score range for the grade (A is 90-100, B is 80-90…)

Have the script output an error message if grade is anything except A,B,C,D,E (add more letters to the grade vector to test this out)

D) The following line creates a random number between -30 and 120 and saves it to the variable temperature:

temperature = sample(-30:120, size=1);- Use the above line and have the script output:

“cold” if the temperature is between -20 and 30 (exclusive of -20 and 30)

“warm” if the temperature is between 30 and 60 (inclusive of 30, exclusive of 60)

“hot” if the temperature is between 60 and 100 (inclusive of 60 and inclusive of 100)

“invalid value” if the temperature is below -20 or above 100

hint: do the if-else-if structure strictly in ascending order or strictly in descending order. This mean splitting the “invalid” category into two conditions (less than -20 and greater then 100)

- Challenge: In the same script – change the output if the user enters a “border” value (in this case: 30 or 60)

- for 30 output: “cold-ish”

- for 60 output: “hot-ish”

E) Repeat parts C, D, and E from the application in last lesson (1-08: Conditional Operations) using if-else statements. Note: there are a few different ways to do this.

Save the script as app1-09.r in your scripts folder and email your Project Folder to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

Instructions for zipping the Project Folder are here.

If you have any questions regarding this application, feel free to email them to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

9.1 Questions to answer

Answer the following in comments inside your application script:

What was your level of comfort with the lesson/application?

What areas of the lesson/application confused or still confuses you?

What are some things you would like to know more about that is related to, but not covered in, this lesson?

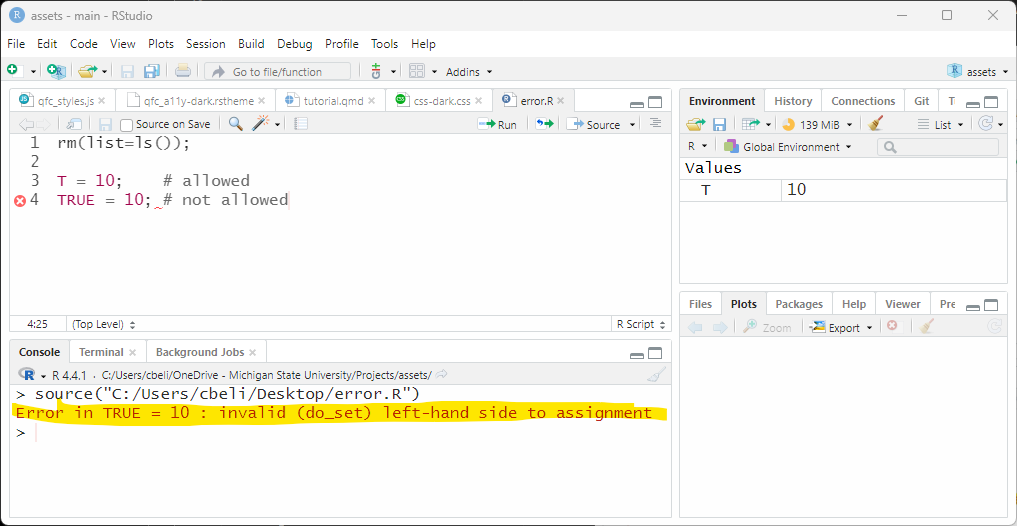

10 Trap: TRUE and FALSE are keywords, T and F are not

The terms TRUE and FALSE are reserved keywords in R – this means that TRUE and FALSE are predefined and cannot be used as variable names in R.

If you try to assign a value to a “variable” named TRUE or FALSE, you will get an invalid (do_set) left-hand side to assignment error (Figure 9). This is the same error you get if you try to assign a value to a number (e.g., 10 = “a”).

You will often see R scripts that use T and F as shortcuts for TRUE and FALSE. R accepts T and F as shortcuts for TRUE and FALS but T and F are not keywords. This means that someone can assign a value to T or F that overrides the default TRUE/FALSE values – as done in Figure 9. If this happens, using T or F as shortcuts for TRUE or FALSE would produce unexpected results. It is best to stick with the reserved (and protected) keywords TRUE and FALSE.

11 Extension: brackets and code blocks

A codeblock enclosed by curly brackets { } usually follows an if() statement. The brackets designate the start and end of the code block and R does not care how the brackets are placed in code – as long as the order is correct.

The following four code-blocks all execute exactly the same in R:

rm(list=ls());

yourAge = readline("How old are you? ")

if(yourAge < 20)

«{»

cat("You have your whole life ahead of you!!");

«}»rm(list=ls());

yourAge = readline("How old are you? ")

if(yourAge < 20)«{»

cat("You have your whole life ahead of you!!");

«}»rm(list=ls());

yourAge = readline("How old are you? ")

if(yourAge < 20)«{» cat("You have your whole life ahead of you!!"); «}»rm(list=ls());

yourAge = readline("How old are you? ")

if(yourAge < 20)

«{»

cat("You have your whole life ahead of you!!"); «}» All the above code blocks are valid. R just looks for a start and end bracket and executes everything in between – it completely ignores the spaces in between. The decision on where to place the brackets has to do with coding standards and viewability. The first two code blocks above are the most commonly accepted standards and your code should use one of these two methods.

12 Extension: Skipping brackets in if-else structures

You will often see if-else statements with no curly brackets. This only works if there is only one command attached to the if() and one command attached to the else.

rm(list=ls());

favAnimal = readline("What is your favorite animal? ");

if(favAnimal == "Llama")

cat("You are wise beyond your years");

else

cat("You still have a lot of room for growth");The code above works and is functionally equivalent to the code below

rm(list=ls());

favAnimal = readline("What is your favorite animal? ");

if(favAnimal == "Llama")

{

cat("You are wise beyond your years");

}else

{

cat("You still have a lot of room for growth");

}The only advantage to not using curly brackets is that it takes up less space. I recommend that you include curly brackets even if there is only one command in the codeblock – it is more explicit and you avoid errors later on.

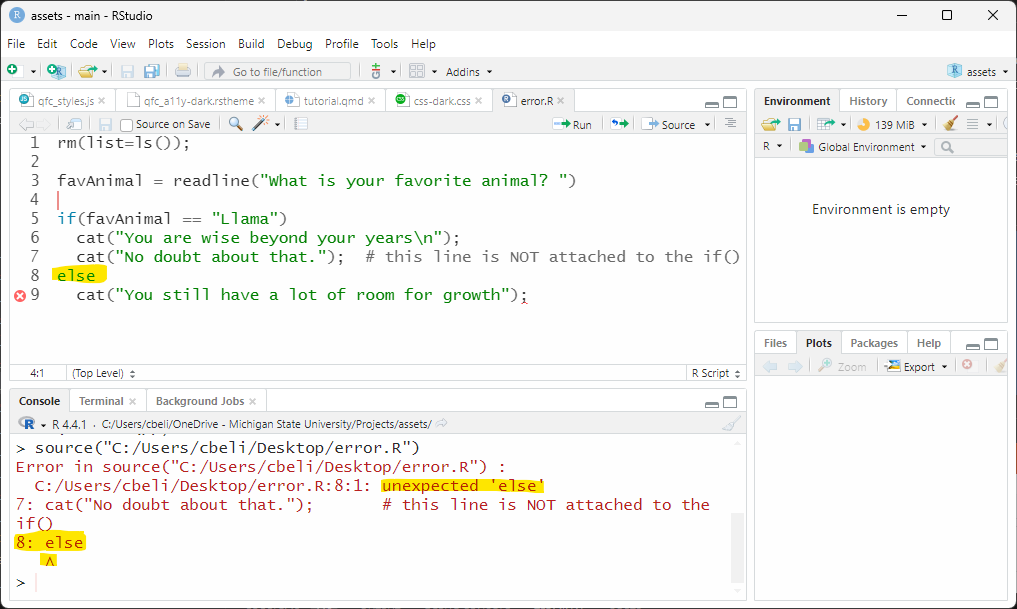

The code below will give an unexpected ‘else’ error. This is because R believes that the if() structure ends right after the first command, the cat() on line 7, because there are no curly brackets attached to the if(). This means the else statement is completely detached from the if(), so the else was unexpected.

rm(list=ls()); options(show.error.locations = TRUE);

favAnimal = readline("What is your favorite animal? ")

if(favAnimal == "Llama")

cat("You are wise beyond your years\n");

cat("No doubt about that."); # this line is NOT attached to the if()

else

cat("You still have a lot of room for growth");

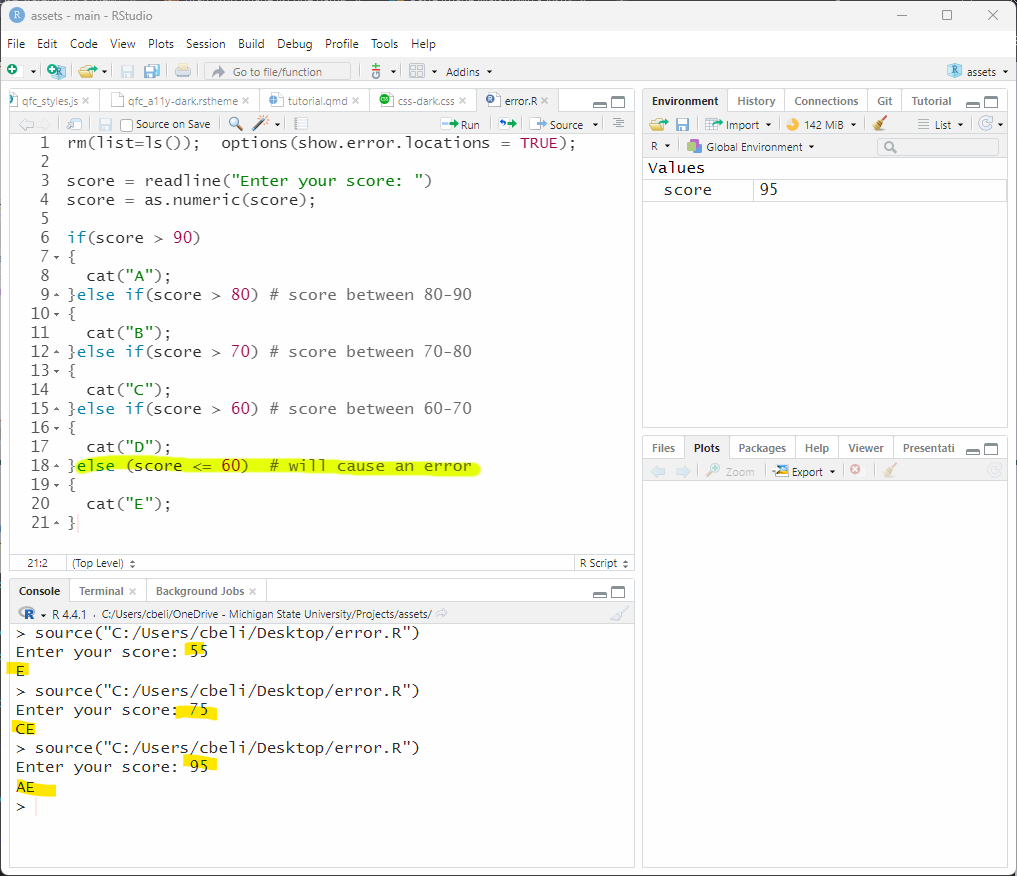

13 Trap: else never has an attached condition

A common mistake for people new to programming is to treat else like an if() or an else if() and attach a condition to it. The codeblock attached to the else statement is supposed to be executed if all other conditional statements in the if-else-if structure fail.

rm(list=ls());

score = readline("Enter your score: ")

score = as.numeric(score);

if(score > 90)

{

cat("A");

}else if(score > 80) # score between 80-90

{

cat("B");

}else if(score > 70) # score between 70-80

{

cat("C");

}else if(score > 60) # score between 60-70

{

cat("D");

}else (score <= 60) # will cause an error

{

cat("E");

}The script seems to work at first. If you type in a value below 55 then “E” will be the output. However, if you type in 75 the output is “CE”. If you type in 95 the output is “AE”. In fact, “E” will be part of the output no matter what you type in.

What happens is that the errant condition (score <= 60) was attached to the else instead of the codeblock. Since the codeblock below was was detached from the else statement, it execute without condition (i.e., all the time).

{

cat("E");

}The proper way to code the else is as follows:

rm(list=ls());

score = readline("Enter your score: ");

score = as.numeric(score);

if(score > 90)

{

cat("A");

}else if(score > 80) # score between 80-90

{

cat("B");

}else if(score > 70) # score between 70-80

{

cat("C");

}else if(score > 60) # score between 60-70

{

cat("D");

}«else» # all other conditions failed

{

cat("E")

}Now the else will execute only when all other conditions fail. In other words, it will execute when score is less than or equal to 60

14 Extension: Programming standards for if-else statements

Neither Figure 1 or Figure 2 is the programming standard for coding an if-else structure. The two most common methods put else on a line by itself either like this:

if(randomNum2 > 50)

{

cat("You win");

}

else

{

cat("You lose");

}Or like this:

if(randomNum2 > 50) {

cat("You win");

}

else {

cat("You lose");

}I would argue that these methods above improve upon the R standard for coding if-else structure. The problem is that, in R, the above methods will occasionally cause an unexpected ‘else’ error. The reason why gets deep into the weeds of R.