1-13: User Created Functions

0.1 Future changes

- break up app #3

1 Purpose

Create reusable code (a function)

Use arguments in functions

Use return values in functions

2 Questions about the material…

The files for this lesson:

Main Script: download the main script here

Function Script: download the function script here

If you have any questions about the material in this lesson, feel free to email them to the instructor, Charlie Belinsky, at belinsky@msu.edu.

3 Four structures in programming

Once again, there are basically 4 main structures that cover almost every aspect of programming:

Variables

If-Else Statements

For Loops

Functions

And now we have reached the last structure: functions, which we will cover in the next few lessons. Functions allow you to write code once and reuse it as opposed to writing the same code multiple times.

4 Reusable scripts

Functions are self-contained codeblocks that performs a common task. For example, there are statistical functions that take a vector of values and return the statistical value (e.g., mean() and median()), functions that take data and create plots (e.g., plot(), boxplot()), and functions that interact with the Console (e.g., cat() and print()). The functions listed above are come with R and are designed to be used in any script.

Broadly, there are three types of functions in R:

1) Base-R: these are function that come with R (e.g., mean(), median(), boxplot(), cat())

- We covered these in lesson 1-05, and there is more here: Extension: The R-base mean() function

2) Packages: extensions of R (e.g., ggplot2, tidyverse – covered later in class)

3) User-created: the main focus of the next few lessons

5 Using a function script

There are two script files in this lesson:

1-13_Functions_Only.R: This script contains only user-generated functions

1-13_Functions_Main.R: The main script that makes use of the functions in 1-13_Functions_Only.R

So far we have used base-R functions. Now we are going to create our own (user-generated) functions. In general user-created functions are put in a separate script. This is done so that the functions can be used by multiple scripts, just like base-R functions can be used by any script.

Because the functions are in a separate script, we must first read (source) the functions script from the main script before we can use the functions:

This line in 1-13_Functions_Main.R executes all code within the script 1-13_Functions_Only.R (assuming it is in the scripts folder inside your project folder):

source("scripts/1-13_Functions_Only.R");R will put the three functions from 1-13_Functions_Only.R into the Environment:

hello_you: function (who, feeling_good = TRUE)

mean_advanced: function (vec, removeNA = FALSE)

mean_simple: function (vec)Functions, like variables, are named objects that store information. The difference is that variables store values whereas functions store script. User-generated functions must be in the Environment before they can be used.

5.1 Clearing the Environment

In all the precious lessons, every script includes this code at the top:

rm(list=ls())The purpose of this code is to clear out your Environment so that your script has a clean slate. In reality, it is to force programmers to include all the resources they need to run a script inside the script they are running (i.e., make the script self-contained). However, function scripts are resources for the main script and calling rm(list=ls()) from the function script would clear the Environment of variables declared in the main script. A function script should never clear the Environment.

6 Function components

All functions, whether base-R, in packages, or user-created, have the same four components: name, arguments, codeblock, and return value.

Let’s start with the simplest function in 1-13_Functions_Only.R. This function is named hello_you(), has two arguments: who and feeling_good, and returns msg to the caller.

«hello_you» = function(«who», «feeling_good»=TRUE)

{ # start codeblock

msg = paste0("Hello, ", who)

if(feeling_good == FALSE)

{

msg = paste0(msg, ", I'm sorry you are not feeling well today!")

}

return(«msg»);

} # end codeblocknote: when referring to a function name, we usually add ( ) to differentiate it from a variable

6.1 function codeblock

Functions, just like if() and for(), have codeblocks attached to them that are executed when the function is called. The codeblock is encapsulated with curly brackets { }.

A function codeblock operates like any other R code with two exceptions:

The arguments in the function call (e.g., who and feeling_good) are variables used in the codeblock.

Functions usually return a value (e.g., msg) to the caller using return().

6.2 Setting argument values

hello_you() is in the Environment so we can now call it in 1-13_Functions_Main.R. Let’s first call the function using only the who argument:

hi1 = hello_you("Bob");

hi2 = hello_you(who="Charlie");hi1: "Hello, Bob"

hi2: "Hello, Charlie"Since who is the first argument in hello_you(), R assumes the first value (i.e., “Bob”), if unnamed, is for the first argument . We can also explicitly name the argument (i.e., who=“Charlie”).

In both cases, the function call is assigned to a variable (hi1, hi2). This means that the return value of the function is assigned to the variable (e.g., msg).

Note: if hello_you() is in the Environment, then you can also call it in the Console:

> hello_you("Brad")

[1] "Hello, Brad"

> hello_you(who="Chuck")

[1] "Hello, Chuck"In this case, the return value, msg, in outputted to the Console

6.3 Default values

Most functions in R have default values for some of the argument. In hello_you(), feeling_good has the default value of TRUE. The caller must provide values for arguments that do not have default values and functions often have numerous arguments. In order to avoid overwhelming the caller, default values are provided for most arguments.

Looking at the Help for boxplot(), we see that the Default S3 Method has many arguments but all of them, except x, has a default value. x is the data and the rest of the argument are tweaks to the function.

## Default S3 method:

boxplot(«x», ..., range = 1.5, width = NULL, varwidth = FALSE,

notch = FALSE, outline = TRUE, names, plot = TRUE,

border = par("fg"), col = "lightgray", log = "",

pars = list(boxwex = 0.8, staplewex = 0.5, outwex = 0.5),

ann = !add, horizontal = FALSE, add = FALSE, at = NULL)6.4 Changing default values

Default values are generally what the programmer consider to be the most common values for the argument. In the case of hello_you(), we are assuming that the majority of people are feeling good so the the default value is TRUE.

If someone is not feeling good, they change the value for the feeling_good argument:

{.r 1-13_Functions_Main.R=""} hi3 = hello_you("David", feeling_good=FALSE); hi4 = hello_you(who="Evelyn", feeling_good=FALSE); hi5 = hello_you("Frank", FALSE); hi6 = hello_you(feeling_good=FALSE, who="George");

hi3: "Hello, David, I'm sorry you are not feeling well today!"

hi4: "Hello, Evelyn, I'm sorry you are not feeling well today!"

hi5: "Hello, Frank, I'm sorry you are not feeling well today!"

hi6: "Hello, George, I'm sorry you are not feeling well today!"note: the caller could set feeling_good to TRUE. It does not change the argument value but it makes the function call more explicit.

6.5 Argument order

In our last example, every function call uses both arguments: who and feeling_good. The argument names are not needed if the arguments are presented in the same order as given in the function:

hi5 = hello_you("Frank", FALSE);On the flip side, using all argument names makes the function call more readable and you do not have to worry about order:

hi4 = hello_you(who="Evelyn", feeling_good=FALSE);

hi6 = hello_you(feeling_good=FALSE, who="George");For many R functions, the first argument is the data, and often left unnamed, whereas the rest of the arguments are typically named:

hi3 = hello_you("David", feeling_good=FALSE);In general, I would argue that arguments beyond the first should be named for readability – especially when you have functions with many arguments.

7 Function header

The other two functions in 1-13_Functions_Only.R calculate the mean of a vector.

The four components of two mean functions are:

name: mean_simple() and mean_advanced()

arguments:

mean_simple() has one: vec

mean_advanced() has two: vec and removeNA

codeblock: everything between ( { ) and ( } ) – this is the code that gets executed when the function is called

return value: both functions return the mean value using return()

8 Using the mean functions

In the Environment, we see that mean_simple() has one argument, vec, that does not have a default value.

mean_simple() solves for the mean by cycling through all the values in vec using a for loop, adds the values, and then divides that by the number of values in vec.

mean_simple = function(«vec»)

{

vecAdded = 0; ### state variable -- starts at 0

### Use the for loop to cycle through all the values in vec and add them to vecAdded

for(i in 1:length(«vec»))

{

### Adds the next value in vec

vecAdded = vecAdded + «vec»[i];

}

### Divide the total value by the number of values to get the mean

meanVal = vecAdded / length(«vec»);

### return the mean value to the caller

return(«meanVal»);

} 8.1 Return value

From the caller’s perspective, a function takes arguments as input and returns a values as output. The return value is sent to the caller using the function return():

return(meanVal);When the caller calls the function, they often set a variable equal to the function (e.g., retVal in the code below). The return value is stored in the variable set equal to the function:

meanSimp1 = mean_simple(c(3,5,2,7)); # saves the return value (4.25) to the variable retVal8.2 Calling the function

We will call mean_simple() multiple times and save the results to four different variables:

meanSimp1 = mean_simple(vec=c(6,2,8,3)); # 4.75

# meanSimp2 = mean_simple(); # error because argument not provided

meanSimp3 = mean_simple(vec=c(6,2, NA, 8,3)); # NA_Real because of the NA

meanSimp4 = mean_simple(vec=c(6,2,8,3,75,200)); # 49

anotherVec = c(7, -7, 10, -8);

meanSimp5 = mean_simple(vec=anotherVec); # can use a predefined vectorEach call to the function mean() passes in a vector of values for the vec argument and saves the return value to a variable (ret2a, ret2b…). In the Environment we can see the return values stored in the variables.

meanSimp1: 4.75

meanSimp2: NA_real_

meanSimp3: 49

meanSimp4: 1note: the mean value of a vector with NA values is NA. This is similar to median() in lesson 1-05. More about that here: Extension: The R-base mean() function

9 mean_advanced

Just like mean_simple(), the function, mean_advanced() solves for the mean by going through all the values in the caller-supplied vector, adding them up, and then dividing that answer by the number of values in vec. The difference is that mean_advanced() checks for NA values and gives the caller the option to remove them.

9.1 Header line of a function

The header for mean_advanced() looks similar to mean_simple() except there is a second argument, removeNA, and this argument has a default value of FALSE. This means if the caller does not set removeNA, it will be FALSE (i.e., NA values will not be removed).

mean_advanced = function(vec, removeNA = FALSE)9.2 Codeblock

In the codeblock attached to mean_advanced(), we need to conditionally handle the situation where NA values are to be removed, based on the value of the argument removeNA. We do this using an if-else-if structure inside the for loop.

mean_advanced = function(vec, removeNA = FALSE)

{

vecAdded = 0; ### state variable -- starts at 0

numNA = 0; ### second state variable that counts the number of NA values

### Use the for loop to cycle through all the values in vec and add them to vecAdded

for(i in 1:length(vec))

{

if(is.na(vec[i]) == FALSE) ### If the value is not NA

{

### Adds the next value in vec

vecAdded = vecAdded + vec[i];

}else if (removeNA == TRUE) ## we have a NA value and want to remove it

{

### Don't add the value, instead increase the number of NA by 1

numNA = numNA +1;

}else if (removeNA == FALSE) ## we have a NA value and don't want to remove it

{

### We cannot solve for a mean with an NA so the return value has to be NA

return(NA_real_); # return() ends the function -- just like break() ends a for loop

}

}

### Divide the total value by the number of values that are not NA to get the mean

meanVal = vecAdded / ( length(vec) - numNA);

### return the mean value to the caller

return(meanVal);

}There are three possible situations, hence three parts to the if-else-if structure:

if(is.na(vec[i]) == FALSE) # The current vec value is not NA- The ith value is not NA (i.e., it’s a number), so add the number to the total

else if (removeNA == TRUE) # We have a NA value and want to remove it- ignore the NA value and add 1 to the number of NA values

else if (removeNA == FALSE) # We have a NA value and don't want to remove it- at this point, we know the return value has to be NA – so return NA

9.3 return() ends the function

Just like break immediately ends a for loop, return() immediately ends a function.

There are two return() statements in this function:

Once an NA value is hit, and the caller did not ask for NA values to be removed. At this point we know the answer is NA. There is no point in checking any more values in the vector. We put a return() to end the function and pass NA back to the caller

At the end of the codeblock after the for loop cycles through all the values in the vector.

Since return() ends a function, only one return() can be executed per function call.

9.4 Using the function

meanAdv1 = mean_advanced(vec=c(6,2,8,3)); # 4.75

# meanAdv2 = mean_advanced(); # will cause error because argument not provided

meanAdv3 = mean_advanced(vec=c(6,2, NA, 8,3)); # will be NA (removeNA default is FALSE)

meanAdv4 = mean_advanced(vec=c(6,2, NA, 8,3), removeNA = TRUE); # 4.75

meanAdv5 = mean_advanced(vec=c(6,2,8,3, 75,200)); # 49Each line of code above calls the function mean_advanced(), passes in values for one or more arguments, and saves the return value from the function to a variable (ret3a, ret3b…). In the Environment we can see the return values stored in the variables.

meanAdv1: 4.75

meanAdv3: NA_real_

meanAdv4: 4.75

meanAdv5: 4910 Application

1) For this application you need to…

Create two scripts:

a functions script named app1-13_functions.r that contains the functions created in this application

a main script named app1-13.r where you will answer questions in comments and test the functions created in app1-13_functions.r

source() your functions script from the main script

Make sure you thoroughly test all the functions you create in your main script. I want to see the test code in app1-13.r.

2) For the function mean_advanced(), answer the following questions in comments in the main script:

Why do we count the number of NAs?

For the two else if statements, what assumption can be made about the ith value being checked? Why can we make this assumption?

Why does removeNA have a default value but vec does not?

Under what circumstances, if any, will this line not be executed?

meanVal = vecAdded / ( length(vec) - numNA);3) Create a function that returns either the standard deviation (default) or variance of a vector:

There should be two arguments: (1) the vector and (2) something that allows the caller choose whether they want the standard deviation or the variance of the vector.

Do not use var() or sd() – use your own formula. You can use the code from the application in lesson 1-03 as a starting point.

4) Create a function that converts a temperature from either Celsius to Fahrenheit (default) or Fahrenheit to Celsius

The conversion from Celsius to Fahrenheit is: \(F=\frac{9}{5} C+32\)

The user needs to pass in two arguments: (1) the temperature value and (2) which direction they want to convert

5) Create a function that takes a single number from 0 to 100 and returns a grade from A to F.

- Return an error if the number is less than 0 and return a different error if the number is greater than 100.

6) Create a function that takes a vector of numbers and returns the percentage of values that are above 60.

Have the function ignore values less than 0 or greater than 100

Test the function with 25 random numbers from -20 to 120

sample(-20:120, size=25);

Save the script as app1-13.r in your scripts folder and email your Project Folder to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

Instructions for zipping the Project Folder are here.

If you have any questions regarding this application, feel free to email them to Charlie Belinsky at belinsky@msu.edu.

10.1 Questions to answer

Answer the following in comments inside your application script:

What was your level of comfort with the lesson/application?

What areas of the lesson/application confused or still confuses you?

What are some things you would like to know more about that is related to, but not covered in, this lesson?

11 Extension: Functions without arguments

Most of the time you need to include arguments when you call a function.

There are exceptions. For instance c(), which creates a vector, is often used without an argument, which means the vector initially has no values (i.e., a NULL vector):

vec1 = c(); # a vector that initially has no values (an empty vector)

vec2 = c(5,2,9,1); # a vector with four valuesvec1: NULL

vec2: num [1:4] 5 2 9 1You could also call cat() without any arguments, and R will display nothing:

> cat()

> date() is a simple enough function that you do not need any arguments:

> date()

[1] "Fri Sep 19 10:17:29 2025"12 Extension: The R-base mean() function

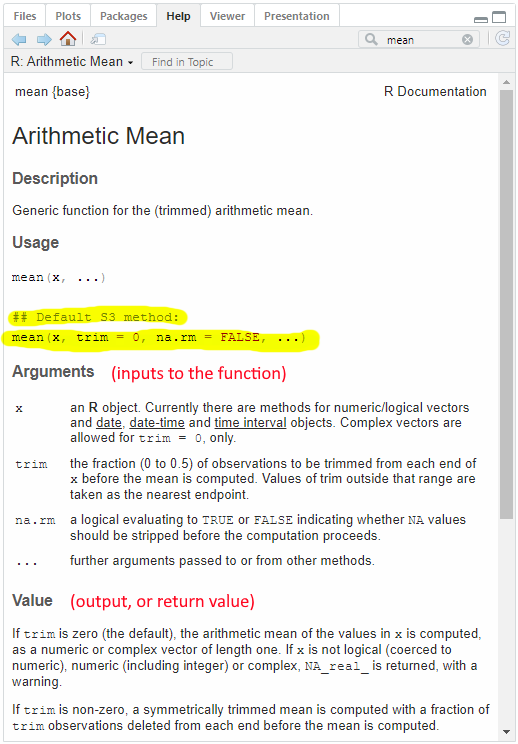

For a little refresher of R-base functions and their components, let’s look at the built-in R function mean(). When calling a function, there are three things the caller must know: name, arguments, and return value. The Help tab for a function gives these:

12.1 Name

Functions, like variables, are named objects that stores information. The difference is that variables store values whereas functions store script.

The name of the function in Figure 1 is mean(). When referring to a function, we often put parentheses after the name to indicate that this object is a function, not a variable.

12.2 Arguments (inputs to a function)

Arguments are variables whose values are supplied by the caller and used by the function.

In the Help tab (Figure 1) we see that the Default S3 Method (the most commonly used method) for mean() has three arguments (x, trim, na.rm).

mean(x, trim = 0, na.rm = FALSE, ...)In this case, x is the vector of values that the caller want to find the mean for. Note: x is often used by R as a generic argument for input values.

The other two arguments, trim and na.rm, are tweaks to mean() that give mean() more functionality. trim can be used to remove extreme values and na.rm can be used to ignore NA values. trim and na.rm have default values (trim = 0, na.rm= FALSE) meaning the caller does not need to provide values for these arguments unless they want to change the default functionality of mean().

12.3 Return value (output of a function)

When a caller calls a function, they usually expect to get some information back from the function. In the case of mean(), the caller is expecting the mean value of the vector provided as an argument. The Value section of Figure 1 gives information about what the function is returning to the caller. mean() returns a length-one object.

In other words, the return value from mean() is one value: the mean.

12.4 Using a function

We will call mean() multiple times with the same vector of values but changing the arguments. One value in the vector is NA, which we need to deal with because the mean of any vector with an NA value is NA. Note: this was covered in more detail in lesson 5 with median().

There are four calls below to the function mean(). Each call passes in one or more argument value, and saves the return value from the function to the variables named meanBase1, meanBase2, meanBase3, and meanBase4.

testVector = c(10, 15, 5, NA, -100, 10); # has an NA value

meanBase1 = mean(x=testVector); # uses default for na.rm, which is FALSE

meanBase2 = mean(x=testVector, na.rm=FALSE); # same as above

meanBase3 = mean(x=testVector, na.rm=TRUE); # remove NAs

meanBase4 = mean(x=testVector, na.rm=TRUE, trim=0.1); # remove NAs and trims high and low valueIn the Environment we can see the return values stored in the variables.

meanBase1: NA_real_

meanBase2: NA_real_

meanBase3: -12

meanBase4: 10meanBase1 and meanBase2 are NA_real because there was an unignored NA value in the vector and we did not choose to remove the NA. note: NA_real_ means the value is NA but would be a real number if it was not NA.

meanBase3 is -12, the mean of the values when the NA is removed

meanBase4 is 10, the mean of the values when the high (15) and low (-100) values are also removed. Note: trim=0.1 means trim top and bottom 10%.